A Small Coin Reveals a Big Secret

In the early 1980s, Grand Turk dive operator Mike Spillar was cruising around the islands, diving with some friends.

By Donald H. Keith

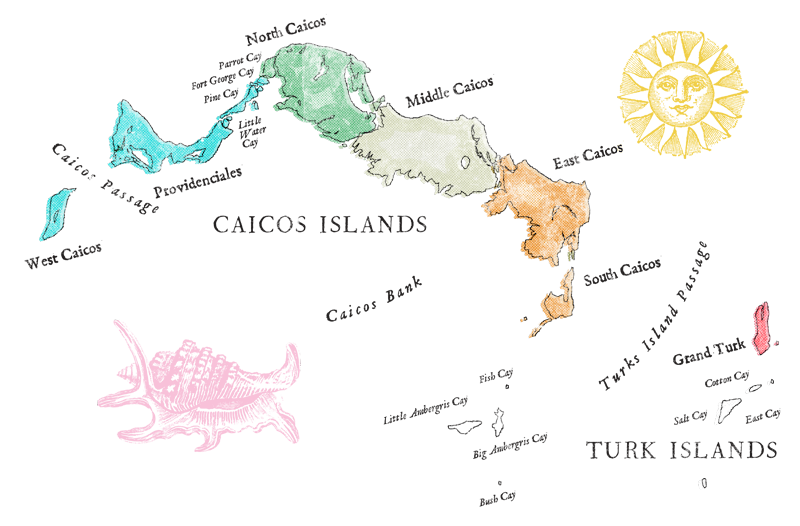

In the early 1980s, Grand Turk dive operator Mike Spillar was cruising around the islands, diving with some friends. After a dive on the west coast of West Caicos, the group motored to shore, hoping to find a place to land. But that side of the island, unprotected by a fringing reef and often scourged by the full force of the sea, offers no beach, only the ragged, eroded limestone formations called ironshore. Not willing to risk the dingy, they were about to turn back when they spotted a natural cove large enough to enter and tie up in protected waters.

Once on shore, they were delighted to discover pools of fresh water that had accumulated in natural basins in the rock. The shallow pools were tepid, but fresh and inviting. Mike stretched out in one to rinse off. Then, in water only a few inches deep, something caught his eye. It was a small, irregularly-shaped piece of metal, hardly worth a second glance. Mike had recently participated in the excavation of a shipwreck on Molasses Reef only a few miles to the east. Maybe it was that experience, maybe it was just dumb luck, but an inner voice told Mike that the little piece of metal might be important. So he put it in his pocket.

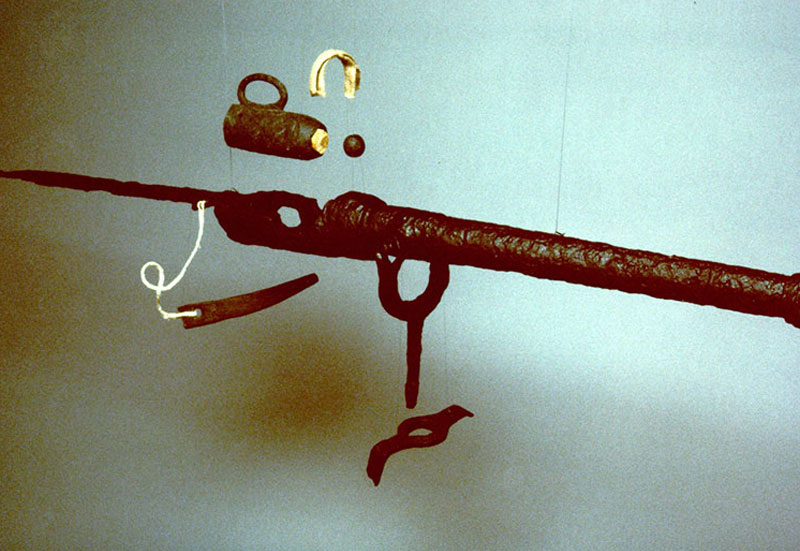

Mike kept his find on top of his dresser, along with scattered small change, rubber o-rings, and all the other things that a dive operator’s pockets disgorge at the end of the day. Mike decided to give it to the archaeologist he had worked with on Molasses Reef. The item was so badly corroded and misshapen that we could only be certain of one thing: it was made of copper.

Back at the lab a few days later, the mysterious artifact turned out to be what we had hoped it would be — a coin. But not the English penny or American one cent piece we might have expected. A Spanish coin. Even more astounding, it was not a common silver piece-of-eight or a gold doubloon, but a copper Carlos y Juana 4-maravedi piece of the so-called “Santo Domingo Series.”

Our astonishment and delight did not stem from the coin’s value. In the early 16th century, a maravedi was worth about 1/34 of a real. In other words, one would need 272 maravedis, or 68 coins like this one, to equal the value of a single piece-of-eight (eight real coin). No, the coin’s significance was its rarity and its date. Although there is some controversy as to exactly where and when coins of this series were minted, it was most likely made in Santo Domingo between 1542 and 1558.

With only brief exceptions, West Caicos has been uninhabited for most of the last five centuries. How did the coin wind up in such an exposed location on the ironshore? Is it really evidence that 16th-century Spanish explorers were once on the island?

What—other than shipwreck—would have brought them there?

During the excavation of the Molasses Reef Wreck in 1982, my colleagues and I spent many months anchored near the site on the southern rim of the Caicos Bank. We could tell from the distribution and type of artifacts that at least some of the crew survived the shipwreck, and we wondered where they might have gone. The only islands visible from the reef are French Cay and West Caicos. French Cay is little more than a sand dune. West Caicos, located about 10 km to the west-northwest downwind and down current from Molasses Reef, is much more likely to have attracted survivors. Even if the ship’s boats were lost during the wreck, the crew could have drifted to West Caicos in a few hours using only makeshift rafts. While the range of dates for the coin Mike found is too recent for it to be connected with the Molasses Reef Wreck, we began to plan a trip to West Caicos to re-locate and survey Maravedi Cove, as we called the site.

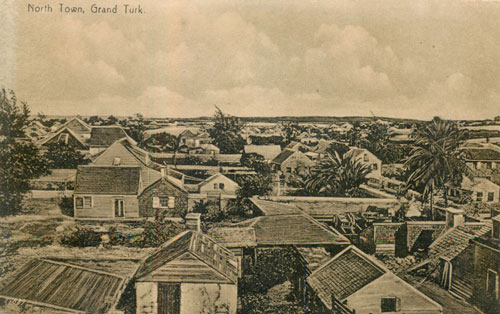

Yankee Town

Our first trip to West Caicos in June of 1984 was memorable. The principal objective was to re-locate the place where the coin was found. We had only two clues: Mike Spillar’s memory and a photograph of the cove taken at the time he was there and used to illustrate an article about the Turks and Caicos Islands in Sport Diver magazine. Five of us spent four days exploring the island by land and by sea, looking for the elusive Maravedi Cove. In the process, we also found the forlorn relics of other, more recent attempts to colonize the island over the last century and a half.

The most striking of these discoveries is the ruins of what people in the Turks and Caicos call Yankee Town. From the sea, Yankee Town is hard to find, even when you know where to look. Wayne, who had been there before, knew to look for the weathered, truncated remains of a stone wharf or jetty so perfectly blended into the ironshore that they are now nearly invisible. A regular pattern of dark patches on the seabed marching out into deeper water suggests that the wharf once extended much farther.

Once we were on shore, the upper walls of the ruins of Yankee Town, a short distance from shore, drew us through the low bush with an irresistible attraction. As we prowled among the scattered ruins, looking for a clearing to make camp, the sky clouded over and a sudden rain squall blew in, soaking us and most of our gear. When it cleared again, we wasted no time setting up the tent and draping a tarp over one corner of a ruined building for equipment storage. Later that day, we made a forced march along the ironshore to the extreme southern tip of the island in a fruitless attempt to locate Maravedi Cove. Sunburned, footsore, and dehydrated, we returned to camp empty-handed. In the early evening light, Yankee Town has an eeriness to it—too quiet and somehow melancholy. The roofless walls and abandoned machinery reminded me of bones bleached by the sun, an elephants’ graveyard.

The expedition cook by default, I tried to incorporate the conch Dennis and Mike caught fresh into a kind of stew, but the mysteries of conch cuisine and inadequacy of our equipment conspired to insure a very late, very bad dinner. Rain blew in and imprisoned us beneath the tarp for the better part of an hour while darkness fell. Then the mosquitoes moved in for the kill, giving us a choice between standing in the rain or being drained of blood under the tarp.

I was better prepared to find Maravedi Cove on a second trip to West Caicos a year later. Determined to learn more about the island and its episodes of human inhabitation, I brought a complete set of backpacking gear and enough water to stay on West Caicos for a week. The plan was for Wayne, Dennis, and his wife, Peggy, to drop me off on the west coast and pick me up a week later at Yankee Town.

The first objective was still to find Maravedi Cove. Fortunately, the photographer who had taken the picture we were using to try to re-locate the site gave us two important tips. First, the picture in the magazine was printed left-to-right reversed. What we were really looking for was its mirror image! Second, we would know we were in the right spot if we could find names carved into the rocks around the pools. Holding the magazine photo up to the light and looking at it from the back side, we found the small, protected cove in the ironshore almost immediately. Then we saw the pools and the carvings on the rocks beside it.

While Wayne and I searched the pool with a metal detector, Peggy strolled into the dense bush behind the ironshore. Wayne and I came up empty-handed using the metal detector, so we turned our attention to the carvings, which were in places heavily weathered, almost obliterated. Still, we could make out clearly four names and three dates. A certain C.B. Selver, someone named Ballerau, and the captain of a ship named La Guerriere (or possibly Cuerriere) were the earliest visitors, on March 10, 1808. T.H.DD. Selver and A. Spencer passed through on September 16, 1860. Then there was a curious inscription which indicates that C.B. [S]elver returned again in “JEN” (January?), 1900—92 years after his first visit! More likely, the second visit was by a son or grandson (the Selvers were an important family in the Turks and Caicos in the last century).

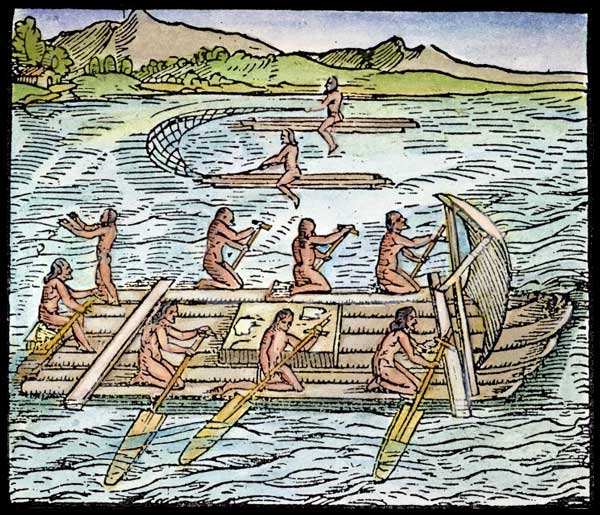

Our musings were cut short by cries from the bush. Using her training as an archaeologist, Peggy had made an even more surprising discovery. In the sand between the stunted bushes, she found tiny, coarse ceramic fragments—potshards! The shards were small, but a peculiarity in the material used to make them—crushed shell in the clay—meant there was no mistaking their origin. The nondescript lumps in Peggy’s hand were the remains of pottery made by the first humans to occupy the Turks and Caicos Islands, the Lucayans, who arrived as early as AD 700.

The mystery of Maravedi Cove was steadily growing more complex. We came to test the site for other evidence of early Spanish occupation, but now we had a mid-16th century Spanish coin, Lucayan pottery, and 19th-century rock carvings—all in the same place. Faint, but definite evidence that something here has been attracting people for at least the last 500 years. We looked around. Was it the tiny natural cove where we tied up our boat? Was it the rainwater collection pools? Was it something else we could not see? Wayne, Dennis, and Peggy headed back to Provo. For a couple of days, I made good progress mapping and photographing the locations of old foundations, wells, curious grooves cut into the ironshore, and various steam pumps and engines scattered through the bush.

Then fate intervened.

On the evening of the third day, a small plane appeared from nowhere, waggling its wings as it made a low pass over my camp on the beach at Logwood Point. On the second pass the passenger’s door opened and a bottle dropped out, landing on the beach a few yards away. Astonished, I saw there was a note in the bottle:

Hurricane on possible course to us, maybe one and a half to two days out. It could be moving faster. Wayne is in route to you. We will radio your position to him. Prepare to leave. Signal fire may be necessary. —Dennis

A few hours later I was in Wayne’s boat, heading back to Provo to prepare for the arrival of hurricane Gloria. The solution to the mystery of Maravedi Cove would have to wait.

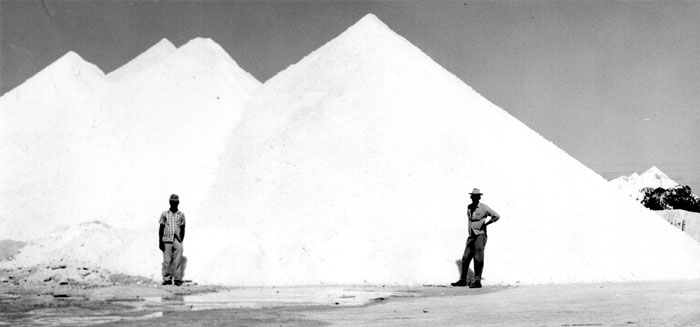

Although no further archaeological surveys have been conducted on West Caicos, we have learned more in a roundabout way. Just last year, we stumbled onto a letter concerning Belle Isle Salt Manufacturing Company written in 1863 by John E. Newport, U.S. Consul to the Turks Islands, to William Seward, President Lincoln’s Secretary of State. The letter explains the origin of the name Yankee Town.

Although the original Belle Isle Salt Manufacturing Company seems to have lasted only three years at best, the site was re-occupied half a century later when an agricultural scheme was introduced. Over the 13-year period between 1890 and 1903, as much as 1,000 acres on West Caicos were cleared and planted in sisal, a plant that produces a fiber used in rope-making. To this day, sisal flourishes in the bush. The ruins of Yankee Town are practically awash in a sea of sisal.

An archaeologist could make a career out of exploring West Caicos. The prospects include prehistoric, relatively undisturbed Lucayan Indian sites; historic survivors’ camps created by the crews of the numerous ships that wrecked on the nearby reefs; and the salt manufacturing and agricultural operations of the last century. West Caicos even has a place in literary and cinematic history: its desolate ruins and ever-present veil of mystery inspired novelist Peter Benchley’s yarn, Island, about a band of modern-day pirates cut off from the rest of the world.

In the fullness of time, with more archaeological investigation and historical research, it is entirely possible that the truth about West Caicos will be even stranger than fiction.

Meanwhile, ospreys continue to elaborate on their nest atop the wall at Yankee Town, flamingos stalk among the abandoned salinas of the Belle Isle Salt Manufacturing Company, snails glide among the broken and fragmented remains of Lucayan pottery, and life goes on quite nicely without the permanent presence of humans on West Caicos—just as it has for thousands of years.