A Slave Account

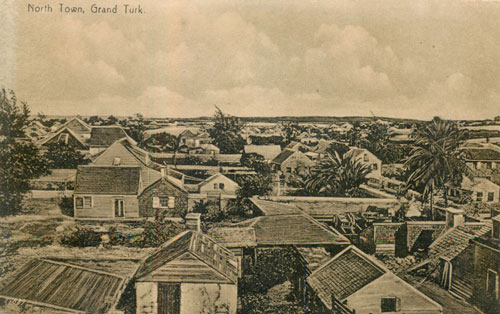

Grand Turk is fortunate in that a first hand record of the treatment and experiences of a slave exists.

Mary Prince’s account as related to Thomas Pringle, who transcribed her recollections and had it published in England in 1831 as part of the Abolitionist movement there, give a detailed, though almost certainly censored, insight into life as a slave in the salt ponds.

It is uncertain who censored the Mary Prince’s recollections. Was it Mary herself trying to hide the full extent of her suffering or was it Thomas Pringle who was trying not to sensationalize Mary’s story to a point where the British public would not believe the horrors she had suffered. In any case Mary Prince’s recollections appeared to have done the job it was intended to: to get the story of slavery to the British audience and to assist in forcing the government to remove slavery from its overseas territories.

Mary was born into slavery in Bermuda. Her early years seemed protected and she even played with the master’s children. However, as she got older she saw the full extent of the horrors of slavery including being sold and split from her family. Further sales saw her move into the ownership of a salt proprietor on Grand Turk. Mary recalled the journey to Grand Turk:

“We were nearly four weeks on the voyage, which was unusually long. Sometimes we had a light breeze, sometimes a great calm, and the ship made no way; so that our provisions and water ran very low, and we were put upon short allowance. I should almost have been starved had it not been for the kindness of a black man called Anthony, and his wife, who had brought their own victuals, and shared them with me”

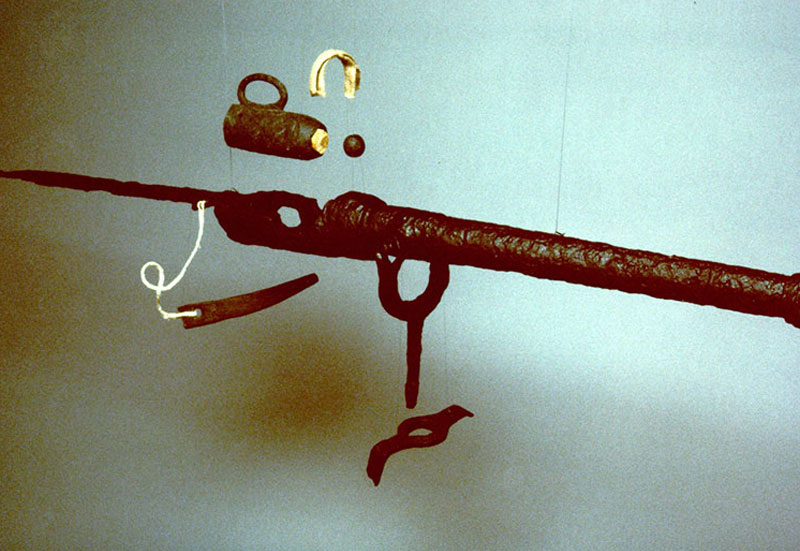

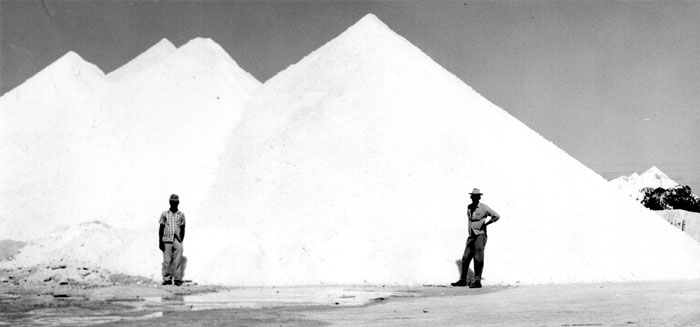

On arrival at “Grand Quay” (Grand Turk) she was handed over to her new Master, Mr D and was valued at 100 pounds. It was clear that life on Grand Turk was harsh. Mary was given a half-barrel and shovel and was expected to work from 4 in the morning. A quick breakfast was taken at 9 am and the she continued working until midday when she was given lunch and then had to return to the salt ponds until dusk. Even then the day’s work was not finished. The salt pond workers were not allowed to work in the ponds between dusk and dawn, but this did not mean they couldn’t work. The salt had to be heaped up, carried to the deposits, bagged up for shipping etc. Mary recalled how hard the life was:

“We slept in a long shed, divided into narrow slips, like the stalls used for cattle. Boards fixed upon stakes driven into the ground, without mat or covering, were our only beds. On Sundays, after we had washed the salt bags, and done other work required of us, we went into the bush and cut the long soft grass, of which we made trusses for our legs and feet to rest upon, for they were so full of the salt boils that we could get no rest lying upon the bare boards”.

She also recalled:

“Sometimes we had to work all night, measuring salt to load a vessel; or turning a machine to draw water out of the sea for the salt-making. Then we had no sleep–no rest–but were forced to work as fast as we could, and go on again all next day the same as usual. Work–work–work–Oh that Turk’s Island was a horrible place! The people in England, I am sure, have never found out what is carried on there. Cruel, horrible place!”

The slaves who worked in the salt ponds ended up with sun blisters on parts of their body that were not covered, and standing for hours in salt water in the ponds caused boils and sores to develop, which never cleared up. Also long term health was affected, and it appears that partial or total blindness was common: Mary Prince allegedly suffered from declining eyesight when she was in England from 1828. It was also clear that the slaves were punished: “If we could not keep up with the rest of the gang of slaves, we were put in the stocks, and severely flogged the next morning”.

She records living in Grand Turk for about 10 years, but like the rest of her accounts there are no fixed dates. However, from her information we can conclude that she probably left in about 1812, as she claims to have received news from slaves on Grand Turk after her return to Bermuda that stated God had been revengeful as the white men would not allow the slaves to build a church, and had washed away all the houses. This is most likely an account of the 1813 hurricane.

Mary’s story continues and sees her being sold to a slave owner in Antigua and then taken to England in 1828 as a domestic servant (slavery was illegal in England and therefore she could not officially be a slave there). As a free person in England she left her Master and it was then she fell into the company of Thomas Pringle.

So who was her Master in the Turks Island? She only recorded her owner as Mr D….., and his son Dickey. It appears that they regularly mistreated their slaves and Mary Prince recorded “He would stand by and give orders for a slave to be cruelly whipped, and assist in the punishment, without moving a muscle of his face”. Mary’s description of her owner does not allow a 100% accurate identification of who he was. The first comprehensive slave records occur in 1822, at least a full 10 years after Mary left Grand Turk, and we must also remember that the 1813 Hurricane would have seen some of the salt pond owners going out of business. However, the slave records do allow us to come up with some very plausible assumptions.

The 1822 slave records Robert and Richard Darrell as being involved in the salt industry and it appears that they were likely to be father and son. Robert is recorded as being in Bermuda, and late (dead) in 1822 and 1825, with Richard (an abbreviated form of Richard is Dickey) being the overseer of the estate, and owning the slaves from 1828.