Putting Right the Wrongs: The Bahamian Archipelago 1807 to 1860

The suppression of the African slave trade was clearly an indicator of the changing reactions and moral direction that the British public had forced the government to take during the first half of the nineteenth century.

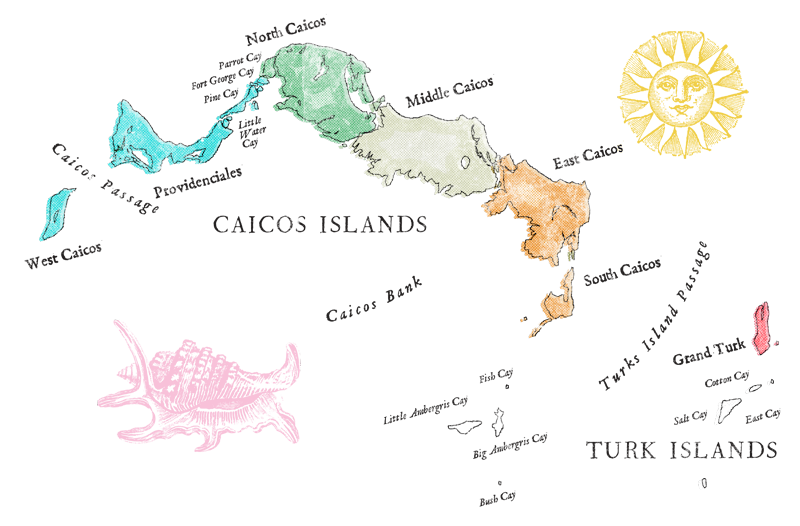

Few people though know of the impact these changes had on the Turks and Caicos Islands

The Political Changes in Britain

By the end of the 18th century opposition to the inhumane slave trade grew and by the early 19th century many European nations were contemplating abolishing slavery. Slowly, one by one, they began to outlaw the trade of slaves from Africa, but paradoxically many did not outlaw ownership of slaves, just the trade from Africa.

Britain outlawed the African slave trade and slavery in Britain with an Act in 1807. Unfortunately, slavery was allowed to continue in the British Empire otherwise Britain would lose essential products such as sugar and cotton. The colonies were still able to trade slaves between themselves but could no longer import any from Africa. Slave owners now had to generate natural stabilization of the slave population through better health care, better treatment and increased birth rates.

This period created a strange mix between African descendants still in slavery with few rights, freed slaves with a few more rights and those Africans freed from slave ships who were being given rights and land to survive in their new homeland. One could only imagine what the slaves thought about the liberated Africans who were getting more rights and freedom than they had.

The Royal Navy Anti Slavery Fleet

Even though treaties were signed outlawing the African slave trade many countries failed to enforce their laws. In response Britain set up a navy patrol which, from 1808, tried to stop the transatlantic slave trade by seizing ships carrying slaves from Africa. A series of bilateral treaties allowed the British Navy to search other country’s ships for slaves and courts of mixed commission were established in West Africa, Caribbean and Latin America to adjudicate on captured ships.

Slave ships (Slavers) were happy to gamble on capture as a cargo of slaves sold for a large profit. One estimate was a slave purchased for $20 in Africa could fetch $350 in the Cuban slave markets thus the British navy was a mere nuisance and no real threat to stopping the trade. As more countries joined in the risks of capture increased and as it became more difficult for the better known slavers to pick up slaves on the coast of Africa they turned to piracy and stole the cargoes of other slavers by force.

Following emancipation in British territories in 1834 public support for stopping the African slave trade dwindled. It was costing money to run these patrols, navy crew were being killed and there was little visible support from other countries. Many felt that whilst slavery remained profitable Britain could do little to stop it. Fortunately, the humanitarians won the day and the Navy slavery squadron increased from 6 ships to over 15.

With the closure of the Brazilian slave markets in 1850 Cuba became the last country in the region to have a slave market. Spain, fearing they would lose their colony to the USA finally agreed to an anti slave trade Act in 1866 and the last delivery of slaves to Cuba occurred in 1867. British ships continued to patrol against slavers until the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888 which brought to an end any possibility of transatlantic slave trade.

Between 1807 and 1860 the British Navy seized some 1600 ships and freed 150 000 Africans who were aboard theses vessels but in the same period an estimated 2 737 900 slaves were shipped to the Americas, mostly to Cuba and Brazil.

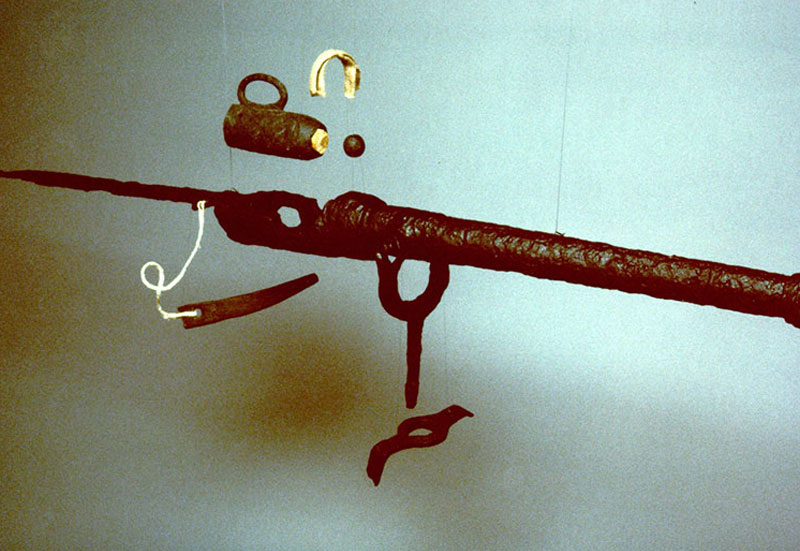

Equipment Clause

Britain was interested in stopping the African slave trade. This would only be possible if they could condemn ships that were equipped to carry slaves, even if no slaves were aboard as well as those with cargoes of slaves. The equipment had to be easy to measure and undisputable and together would condemn a ship for being equipped for carrying slaves. These included:

- gratings to allow for ventilation Instead of slide hatches covering the hold

- extra bulkheads and spare planks for fitting extra tiers in the walls of the hold to increase the carrying capacity.

- iron shackles to fetter the slaves

- supplies of food and water that exceeded the needs of the crew

- cooking boilers and mess tubs for the production of large quantities of food

- native canoes better suited to landing on beaches. If the ship was carrying out legitimate trade it could wait whilst local canoes were loaded and brought out to the ship, but if they were in a hurry to load an illegal cargo it was better for them to carry their own native canoes

Some of these indicators alone could be argued: A ship maybe carrying excessive numbers of empty water caskets for legitimate trade, such as palm oil, so it was the responsibility of the ship’s captain to prove they were to be used for a lawful cargo.

The first agreement covering what equipment designated a slave ship appeared in the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1822 and became known as the “Equipment Clause”. Britain encouraged other countries to accept the equipment clause as an amendment to their existing slavery treaties: Spain accepted it in 1835 and Portugal in 1842, but the French refused to ratify any treaty. Eventually slave ships started to fly the stars and stripes, relying on America’s insistence that only American ships had the authority to board a ship flying the American flag. Eventually America followed suit and one of the most thorough equipment clauses appeared in the Treaty Between Her Majesty and the United States of America For the Suppression of the African Slave Trade. Signed in 1862, this mutually agreed merchant vessels searched could be lawfully detained.

Assimilation into the local Community – Apprenticeship Scheme

Between 1811 and 1860 approximately 6000 Africans came into the Bahamas from 26 captured or wrecked vessels. Technically they were free but as they had illnesses, spoke a range of languages and had a variety of customs they were in no state to be self sufficient. The local government became obliged to look after them and apprenticed them to “prudent and humane masters or mistresses”.

This controversial scheme was not initially accepted and in 1811 a petition was raised, pressing to restrict the numbers of recaptives entering Nassau. Many believed that at the end of the apprenticeship the Africans would turn to begging and crime, putting pressure on the poor relief and creating greater financial burden on the population. They also stated that as the Liberated Africans were not British subjects they had no right to reside in any British territory. Therefore, any imperial attempt to confer that right contrary to the wishes of the Bahamas was against their constitutional rights. There was also an economic concern. The arrival of the liberated Africans would depress the value of slaves as it was more cost effective to pay for labour when required rather than buy a slave.

Eventually, a 7-14 years apprenticeship was introduced during which they learnt English and, as an 1833 contract recorded, were trained “in some art, trade, mystery or occupation” in order to earn a living when their apprenticeship ended. It would also provide them with European social and cultural values, including Christianity. In return for labour, employers were obliged to provide food, accommodation, religious education, medical care and other necessary items.

Even though the scheme was designed to better the Africans many argued it merely provided cheap labour. They were treated no better than slaves, working under similar conditions and given the same rations rather than wages. They were exploited more than slaves because they were available for a limited period, and the apprentice holder had to gain as much as possible before the apprenticeship ended, often at the expense of the African’s moral and intellectual welfare.

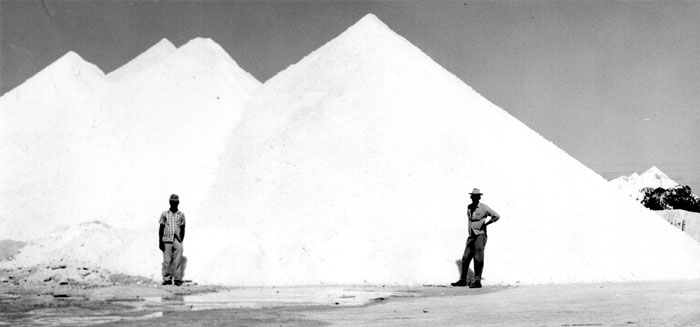

By 1825 many of the first liberated Africans had finished their apprenticeships. Most could eke out a subsistence living, but slave owners believed that this created an African peasantry which undermined the slave society. At the same time Governor Grant suggested that a one year apprenticeship would be long enough especially as the liberated Africans were being hired to carry out harsher jobs than slaves such as salt raking. Later Governors believed the system failed to teach any trade to liberated Africans and was modified slavery.

Following emancipation in 1834 the former slaves entered a 4 year apprenticeship and many believed the liberated Africans should be under the same apprenticeship system. In 1836 Governor Colebrooke stated that 6 months was long enough for adult liberated Africans to acquire the experience to earn a living and to learn English and were to get paid wages as well as their usual provisions.

With the end of apprenticeships for former slaves in 1838 there were strong feelings against keeping any form of involuntary servitude and The Colonial Office decided to dispense with the apprenticeship system. Many Bahamians claimed that apprenticeships were essential to prevent liberated Africans from being enticed away from the colony and into countries still allowing slavery. Colonial Office officials believed such controls was undue interference with their freedom of labor and in 1840 Lord Russell instructed Governor Cockburn that he could hire them out “to service for six or at most 12 months after their arrival, but beyond this you should not interfere with freedom of their labor”. This frustrated Cockburn who saw liberated Africans as an essential labor supply, especially in the salt industry which had difficulty attracting and retaining workers in the harsh working conditions. He had hoped to have them apprenticed for at least 2 or 3 years.

After 1841 the apprenticeship question was not raised again until 1860 when 360 Africans arrived following the wreck of a slaver and a limited apprenticeship scheme was re introduced.

Settlements for Liberated Africans

As the navy’s cat and mouse game with slavers grew the two main areas for contact were off the coast of Africa, and in or near to the Bahamian archipelago. If the ship was captured close to the African coast British ships took them to Sierra Leone, a British Colony where the liberated Africans had some degree of safety and Britain provided for them until they were able to work for themselves.

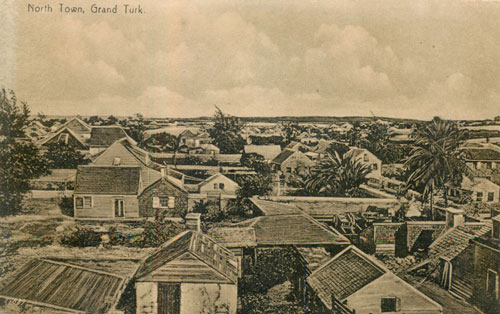

The Bahamian archipelago, containing the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands both British colonies at the time under the control of the Assembly at Nassau, was important due to its closeness to the illegal slave markets in Cuba. The British Navy not only laid in wait in the surrounding waters but also had chance encounters. These captured ships were processed at Nassau.

The burden of looking after many of these Liberated Africans and assimilating them into communities fell on the Bahamas. Arrivals of liberated Africans in the Bahamas peaked in the 1830s, with around 4000 entering between July 1831 and December 1838. Governor Sir James Carmichael Smyth’s solution was to develop settlements on ungranted Crown land where communities of freed Africans could become self sufficient through farming and fishing. New Providence got the majority of liberated Africans and the villages of Headquarters (now Grant’s Town), Adelaide and Carmichael were formed to house them, collectively known as “Over the Hill”. Over the hill was not only a physical place, but also a concept, a divide by the white residents of Nassau from the Africans who became very independent and kept their own languages and customs. Other settlements were set up but with the exception of Grant’s Town were unsuccessful. This was not surprising as the Africans shared no common language nor possessed the knowledge required to make a living from the soil and sea.

There is no evidence of any settlements being set up in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Stipendiary Magistrate, Francis Eve in his 1842 report of the Turks Islands mentions that there were 3 principal settlements in the Caicos Islands but does not name them. One would be the newly formed East Harbour, South Caicos, but could the other two have been for liberated Africans? H E Sadler recorded that Bambarra, Middle Caicos was “established in 1842 by the survivors of the shipwreck Gambia, a Spanish slaver bound for Mexico, the slaves originally coming from the shores of the River Niger”. However, no slaver called the Gambia wrecked in the Bahamian Archipelago between 1807 and 1860 so could this just be confusion over the ship name and the location of the Africans’ origins?

Major Macgregor’s Letter

In the Turks and Caicos Islands these slave ships and liberated Africans was a mixed story. Even though slavery ended in the Turks and Caicos Islands in 1834 nearly all of Liberated Africans arrived here after 1834. The first Liberated Africans to come here were originally from captured slave ships. Between 1833 and 1840, 189 Liberated Africans were transferred from Nassau to the Turks and Caicos Islands. The reason we know about these Africans was because of an incident in 1840.

Major Macgregor had been a Stipendiary Justice in the Bahamas. In 1840 he wrote to Lord John Russell with allegations regarding the treatment of the liberated Africans. Amongst his claims were that there was a higher mortality rate amongst liberated Africans than one would expect and there were instances where liberated Africans had been captured to be taken onto the Cuban slave markets.

Local officials felt indignation to these claims and refuted them. Thorough reports were produced for each Island to show what had happened to the liberated Africans since their arrival on that Island. From these letters it was clear that the local authorities were doing their utmost for the liberated Africans with limited funding and local opposition to the influx.

The response for the Turks and Caicos Islands was formulated by the Stipendiary Magistrate for Grand Turk, Mr Eve. The Report was entitled Return shewing the number of liberated Africans who have been landed at the Turks Islands and Caicos Islands, in the Bahamas, since 1st January 1836, the number at present located there, their distribution, and the cause of diminution, which appears in their numbers and was produced on December 18th 1840. The report was very detailed and listed the name of the employer that the Liberated African had been distributed to, the name of the African, the name of the person employing the African, where they were located (Grand Key, Salt Key or Caicos) and if they had died the date and cause of death.

Using the data collected by Mr Eve and sent to the British Officials by Governor Cockburn, Whitehall Official Mr Spedding wrote on 30th March 1841, “At Turks Island and Caicos, out of 189 that have been received since 1836 there are now 151. Of the remaining 38, 4 are known to have died by shipwreck; 1 on the voyage; 29 from disease (chiefly sea-scurvy). 2 returned to Nassau. 2 only are missing ” and they are supposed to be at the Caicos under other names. Most of the deaths occurred in 1839 and the four who lost their lives in shipwrecks are probably the same four as listed drowned in a Hurricane (shown in the table above). For those still living in the Turks and Caicos Islands in 1840, 72 were on Grand Turk, 43 on Salt Cay and 36 in the Caicos Islands.

From these records we can see most settled in the Turks Islands and probably worked in the salt industry, indicated by the names of the employers they were distributed to or were under contract to. One interesting link is that Richard Darrell is listed as having one of the liberated Africans assigned to him. There is a good chance that Richard Darrell is “Dickey” the son of the owner of Mary Prince whose accounts of her time in slavery helped sway the British population in forcing the government to abolish slavery in 1834.

Lord John Russell decided that Major MacGregor’s claims were unfounded but this investigation did indicate that the liberated Africans had a higher mortality rate than slaves and freed slaves. However, death rates were simply a manifestation of the state of the health of the liberated Africans following their journey across the Atlantic. In most instances liberated Africans travelled on ships that had outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and a whole host of other problems such as inadequate food and water. They arrived in a weakened state and without proper health care could linger and worsen over a few days, weeks, months or even years.

The Esperenza

The most dramatic arrivals of Liberated Africans came from the two slave ships which met their end on the reefs of the Caicos Bank: The Esperenza in 1837 and Trouvadore in 1841.

The Esperenza sank on 10th July 1837. This was its first voyage, setting sail from Africa with a cargo of about 320 slaves. It was sailing under a Portuguese flag and when it wrecked it had a crew of thirty one men and a cargo of two hundred and twenty Africans. Acting Governor Joseph Hunter stated that the Africans landed on “a plantation belonging to Mr Stubbs called the Haulover” on Middle Caicos.

The Captain, with his well armed crew, failed to get the locals to supply a ship to take them onto Cuba, and prepared to seize the first vessel that became available. On hearing of the wrecking the authorities on Grand Turk sent Lieutenant Tew and a detachment of his Majesty’s 2nd West India Regiment to secure the crew and to convey them and the Africans to Nassau.

On arriving in the Caicos Islands Lieutenant Tew took control of the crew and those Africans that were still gathered together. 17 Africans were known to have died on the Caicos islands and “eleven others strayed into the interior, which being covered with bush or jungle, Lieutenant Tew found it impossible to recover them, altho he delayed his departure and had parties out in every direction for that purpose; it is much to be feared therefore that these also will have perished for want of sustenance”. Lieutenant Tew sent the vessel’s sails and rigging to Grand Turk and took the Africans and crew to Nassau “in three sloops hired for the occasion”. Of the 220 Africans that came ashore only 192 started the journey to Nassau. Four died on this journey leaving 129 males and 59 females.

On arriving at Nassau the Africans were sent to the settlement of Roslyn and Joseph Hunter noted that “Many of the survivors were in a very weak and debilitated state from the sufferings to which they had been exposed, but I am happy to find that they are recovering and will be speedily distributed in the outisland districts”. 11 joined the West India Regiment whilst others might have been among the 189 Liberated Africans relocated to the Turks and Caicos Islands in the 1830s.

Around 100 Africans died during the Atlantic crossing. Joseph Hunter wrote that “various and repeated acts of cruelty had been committed by the crew upon the Africans during the passage, many of which amounted to murder”. Unfortunately the authorities could not prosecute the Portuguese crew as the British authorities stated that “Under the treaties with Spain and Portugal, Netherld. and Brazil, the British Govt. cannot detain the crews & make them over to their respective govt. for punishment.”

It was expensive to assist and recover shipwrecked Africans. The Bahamas bore most of the costs and even though the British Government felt that adequate funds were given many Bahamians felt it was insufficient and the Bahamian authorities often requested financial assistance. For the Esperenza the Board of Superintendence of Liberated Africans paid £315 to be divided between the ships owners, captains and crews. Part of the reason for the high costs was that all three ships sent to Nassau sunk in a storm on their return.