Religion & Records

Throughout the West Indies slaves were clearly encouraged to become Christians.

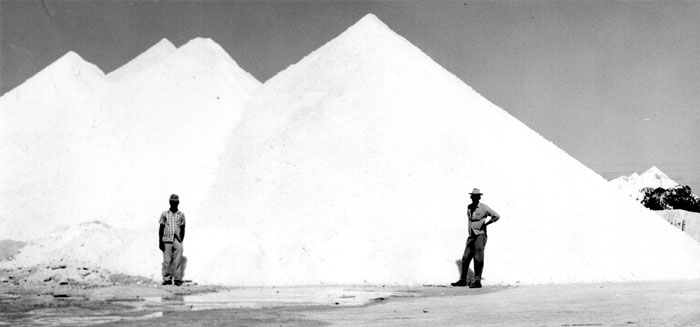

However there were several real issues, one of which was that church allowed the slaves to congregate in large numbers. Mary Prince recorded that “the poor slaves had built up a place with boughs and leaves, where they might meet for prayers, but the white people pulled it down twice, and would not allow them even a shed for prayers”. It seemed to be a strange mix. The Slave owners being God-fearing people wanting slaves to have the same beliefs, yet restricting them practicing their faith and only allowing the religious freedom that they deemed suitable. For example the Sabbath was a day of rest, and in the early Salt Pond Regulations it was against the law for anyone to work in the salt ponds on a Sunday, however, this did not prevent the slaves being forced to work: Mary Prince stated that she had to wash salt bags on Sundays. This was also the only day when the slaves could carry out their own tasks, such as repairing their dwellings, clothes and “relaxing” from the hardship of slavery. This contradictory society, on the one hand the Slave owners declaring to be religious, on the other hand refusing the slaves even the smallest degree of respect seems to run throughout the slave society of the West Indies. It is peculiar that the owners seemed to go through the process of making the slaves legitimate in the eyes of God by baptising the slaves yet limiting their rights to be treated equal and fairly.

We must also remember that most the slave owners worshipped at the established Presbyterian or Anglican churches, whilst the slaves favoured the Baptist or Methodist churches. This made for some alienation between the slave owners and slaves as the owners found Baptist and Methodist church services so different to theirs. In fact Baptists just needed an area to congregate, not necessarily a building, and did not need a qualified priest to read the scriptures: a state of affairs that would have suited the slave community. The Methodist Church caught on because it stressed “freedom” which the Anglican Church suppressed. Dowson, a Methodist Missionary writing in the Turks Islands between 1810 and 1817 stated: “I am told Dalziel never preaches to the slaves and refuses to baptise any of their children without white sponsors I feel a strong desire to preach to the slaves but they seem to take no interest in their salvation” (Peggs, p 37). Rev Thomas Dalziel was the Presbyterian Clergyman, and most of the settlers from Bermuda would have been Presbyterian.

St Thomas’ Parish Records

The early parish records indicate that slaves and freed slaves were being baptised. As stated above, we know that John Lorimer had Rosana baptised in 1800. However, one of the best records in the baptism records is from 1818. During a visit to Grand Turk, Reverend Hepworth, Rector of Christ Church, Nasssau, New Providence baptised 137 “Black and Coloured People free and slaves” (Parish Records pages 137-143). Many of the children have their dates of birth recorded whilst the adults are just recorded as “Adult” under “born” . Unfortunately these records fail to give family relationships: for the white residents they record the names of the child’s parents. This would provide valuable assistance in linking the family ties in the slave records of 1822-1834. However, further work on the parish records should bring to light more slave and freed slave’s names and hopefully link in with those in the slave records for 1822-1834.

The baptism records also help to cast some limited light on other events. We know that the freed slaves from the Trouvadore were supposed to be baptised, but without the slaves names we are unable to identify which “Africans” baptised after 1841 are from the wreck. For example in the following record, are these two children, Joseph and Sambo, part of the Trouvadore slaves? Or does the name Sambo relates to the child’s colour – a Spanish term for a child from a Black-Mulatto union (Edwards, p18).

Marriage Records

In this society the stability of the slave population was most likely to the development of a family structure. We know that children were born here (the baptism records and slave records of 1822-1834 indicate this) but as there was a Christian society wouldn’t we expect the slave owners to have wanted their slaves to be married, to make it official in the eyes of God. However, as of yet there the author has not found any records of an official slave marriage, though there are plenty for the slave owner families for this period. This leads to the question of how the slaves were married. Was it officially by a visiting clergy member or did just the slave owners or members of the slave community carry it out.

Also in law, the slave owner (or owners if it was marriage between estates) had to agree to the wedding, and this agreement was not always forthcoming. This of course does not lessen the fact that the slave communities did try to create stable family lives, with or without the official piece of paper to legitimise their union.

We know that Mary Prince married a freeman after she left the Turks Islands, but only after her owner gave her his permission to do so.

Death records

The slave records of 1825-1834 show that slaves were dying between the record taking, but again the Parish Records fail to record the deaths of slaves.

Another thing that is missing from the slave story is their graves. On none of the Islands have slave graves been identified. It was very likely that they would have had their own designated graveyards, and that the slaves would have been buried rather than cremated, however, they would have had simple headstones, such as a wooden cross, if one at all. These would have quickly deteriorated with the climate and more likely would have been trampled and destroyed by stray donkeys. To really understand their health, medical care and punishment, bones of slaves need to be analysed but of course this leads to the obvious problems.

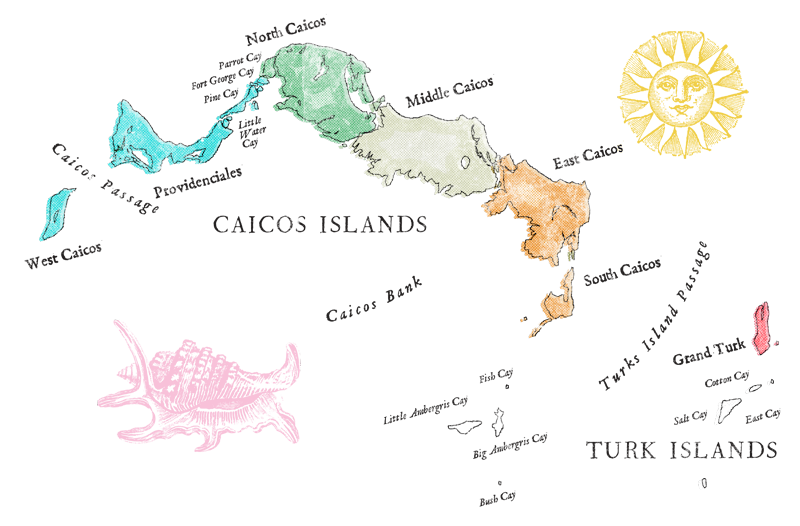

It would be a priority to identify any remaining gravesites linked to the Cotton Plantations in the Caicos Islands, which would probably be easier to locate than possible sites in the Turks Islands. Of course, locating the gravesite would only be the beginning. Firstly the skeletons would need to be found. Secondly the researchers would need to get over any objections that the local community (the descendants) might have by gaining the approval and acceptance of the local population to excavate the remains of their ancestors. Thirdly, a policy would be required for the proper reburial of the remains: they should not become Museum items, or put on display.

The Dowson Accounts, 1811

Slaves developed their own culture based on African food, song and dance, and storytelling but had become corrupted as the slave population changed from being first generation Africans to being born into slavery. In fact it is likely that most of the slaves communities had developed their customs in America (Loyalist slaves) and Bermuda (salt Raking slaves) and these customs had continued to evolve and adapt with the influx of new slaves and the transfer of slaves between estates. Also, the slave accommodation would have been some distance from the slave owners’ house and so they would have had some freedom to express themselves through their own culture, without slave owners fully realising and seeing what was taking place. For this reason little has been recorded about how the slaves spent their spare hours. Of course religion would have played a part in developing the customs, especial aspects of the musical tradition.

Dowson, A Methodist Missionary who worked in the West Indies between 1810 and 1817, arrived in the Turks Islands on Christmas Day, 1811 and recorded, “I never before witnessed such a Christmas Day; the negroes have been beating their tambourines and dancing the whole day and now between eight and nine o’clock they are pursuing their sport as hotly as ever” (Peggs, p36). This is one of the earliest records of Junkanoo in the West Indies, and it clearly shows how secular and religious entertainment becomes mixed. Dowson was upset by the entertainment chosen by the slaves to celebrate Christmas but the Presbyterian clergyman, Dalziel, apologised for them by saying “The week of Christmas is the only time in the whole year in which to be merry and I am pleased to see them enjoy themselves” (Peggs p37). Dowson recorded that he felt “a strong desire to preach to the slaves but they seem to take no interest in their salvation” and on January 1st he stated that he had not been given permission so “cannot preach to the blacks”. This permission was finally granted and on Sunday January 12th he preached “in the house of Mr Thomas Smith to his negroes” and in the afternoon “preached in the barracks to about 250 white, coloured and blacks” but was still not allowed to preach to the slaves by candlelight. During his stay these services became a regular Sunday occurrence.

On February 13th he recorded that “I have expressed my anxiety to instruct the negroes one or two evenings in the week by candle-light and a petition has been presented by several of my friends”. However many were opposed to his plans. This did not prevent him being granted permission. The real obstacle had been that meetings by candlelight elsewhere (England, Scotland and in the West Indies) had been used to plan disturbances. Dowson replied that he wanted to teach them scriptures and that “the word of God cannot influence them to riot” and the acting King’s Agent, John Lorimer, finally gave permission for him to hold meetings between five and six thirty in the evening.

Dowson was at first frustrated and horrified at what he found in the Turks Islands. However, after several Sunday worships his message was getting across. On February 16th he preached to Captain Smith and his slaves and at the end one of the congregation rose up and said, “I will give 100 dollars towards the erection of a chapel” (Pegg p42). Dowson was preparing to leave at this time, but even so subscriptions started to be taken for the construction of a chapel. Because of the donations (mostly in salt) it is likely that the chapel was going to be for the white slave owners rather than the slaves (although it is possible that some slaves and freed black people would have had both salt and money).

Dowson left the Turks Islands at the end of February 1812 and it appears that his stay of only a few months inspired the slaves. We have to ask if it was this visit by Dowson that encouraged the slaves to build a chapel, which according to Mary Prince was pulled down and led to God punishing the slave owners by washing away all their houses.