Two centuries ago, in this very spot, British soldiers endured heat, privation, clouds of mosquitoes, and disease against which they had no defense, laboring to build a military base and shore battery to defend the homes and fields of 40 or so plantation families thinly scattered throughout the Caicos Islands.

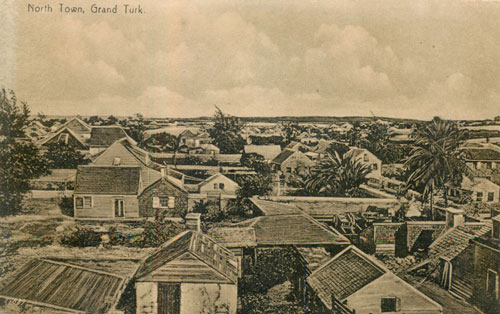

North and Middle Caicos were the population centers in those days, having been settled only a decade or so earlier by Loyalists forced to leave their land when the American rebels succeeded in winning their independence. The plots of land that they occupied and millions of dollars in cash settlements that were given to them were a grateful government’s way of recognizing their loyalty to the Crown and re-compensating them for the sacrifices they made.

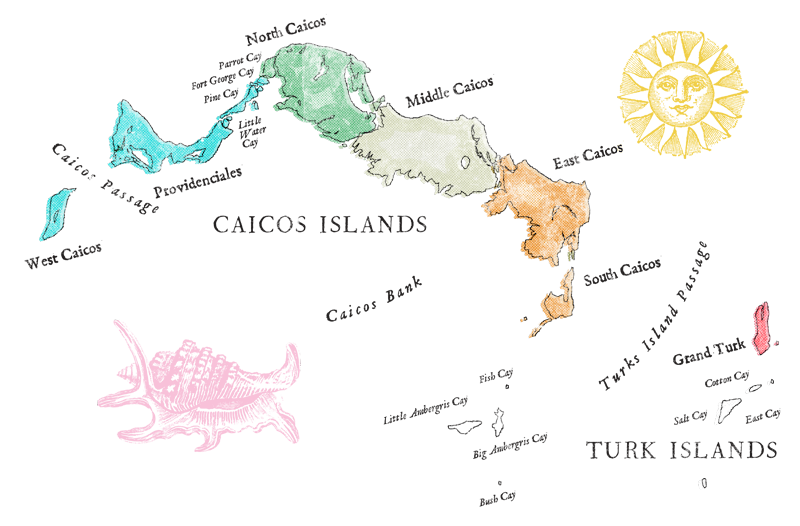

But how did they end up in the Caicos Islands, of all places? It all began in 1783 when Lt. John Wilson was ordered to proceed to the Bahamas, which belonged to the Crown, to make a general survey of the Islands in order to determine where land grants could be made to the Loyalists. Although he visited the Turks Islands he could not make a determination of the population because it varied according to season (like today!), but it seems to have been less than 100. Interestingly, his report does not even mention the Caicos Islands, and from this we may safely assume that they were essentially deserted.

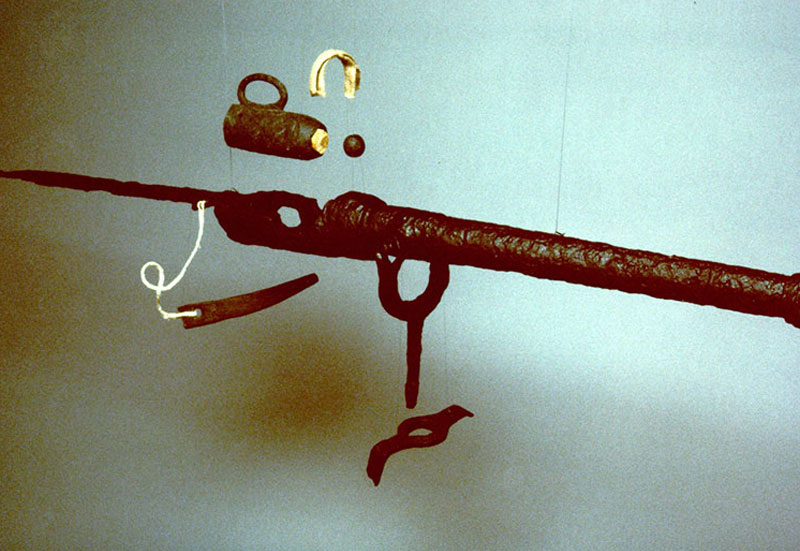

The first Loyalists began to arrive in 1787. During the ensuing plantation period, hundreds of new immigrants cleared huge areas for agriculture and pasture, built imposing structures of stone and wood, planted cotton and sugar cane, and built a road connecting Middle and North Caicos. It is important to appreciate that the Crown had a considerable investment to protect once the Loyalists, their families, and dependents moved to the Islands. When, in the final years of the 18th century, the colonists became concerned that social upheavals in Haiti might result in an attempted invasion, they petitioned the Crown for military assistance. Ft. St. George was the physical manifestation of the Crown’s concern and its effort to reassure the colonists that they would be protected. That the Loyalists did indeed need that protection is substantiated by an incident reported in the Bahama Gazette, August 21, 1798. While attempting to return with cargo salvaged from a supply vessel wrecked near West Caicos, five boats sent by the Caicos Loyalists were attacked by a French privateer. A running gun-battle ensued, unfortunately resulting in the colonists losing not only the salvaged cargo, but also the five boats!

Most of what precious little we know about Ft. St. George comes from the writings of H.E. Sadler, a transplanted Jamaican and amateur historian who wrote copiously about the Turks and Caicos Islands. Unfortunately for us, he never realized the importance of including citations. He could have saved the rest of us an enormous amount of time (and vouchsafed his own conclusions) if only he had mentioned what sources he used. Until those sources can be re-located and verified, it would be wise to approach the “conventional wisdom” about Fort George, most of which comes from Sadler, with a healthy dose of skepticism.

So what do we think we know about Ft. St. George? What authority, other than Sadler, has ever mentioned it at all? How do we know it really existed? What original sources do we have to go on? Sadler gives us the following: Work on Ft. St. George began on December 1798. In one year, the 200-man detachment of the 67th Royal Hampshire Regiment, first commanded by Ensign Neil Campbell and later by “Lieutenant Owen” suffered 15% fatalities, not to combat but to hardship and disease. Sadler says the fort was abandoned in 1799, but research in England uncovered reference to a “large detachment” being sent to the Caicos Islands in September 1797. At the end of 1798 the unit was transferred to Jamaica and in 1801 the 67th Royal Hampshire Regiment shipped back to England—but “some men were left in the Islands.” Yet another contradiction comes from a 1788 London Times article which seems to indicate that Ft. St. George existed 10 years earlier: “The loyalists are men of capital. They have a decent trade with England, receiving their supplies from that quarter and sending in return their sugar and cotton from Ft. St. George.”

Regardless of exactly when the fort came into being, why it was located on the tiny island that subsequently became known as Ft. St. George Cay is less of a mystery: The Cay is perfectly situated to guard the best anchorage for small vessels on the northern side of the Caicos Islands. A passage in the Columbian Navigator of 1856 describes in considerable detail how to find the cut in the reef and where to anchor inside. It makes reference to “A set of chain-moorings [that] were laid down here by a Bahama merchant some years since” which would seem to indicate a relatively high volume of ship traffic. An additional attraction was the availability of fresh water on both Ft. St. George and Pine Cay. “The greatest advantage of Pine’s Kay is a great lagoon of fresh water, sufficient for fifty ships: it is very drinkable, and not far from the beach.”

Land grants made to the Loyalists Missick, Stubbs, Penn, Williamson, and Hyett on Parrot Cay and North Caicos were the closest to Ft. St. George; they and other Loyalist planters undoubtedly depended on it to protect their commerce. The plantation period lasted only a few decades. When the land failed to be as productive as they had hoped, most of the planters departed for greener pastures. Now the only vestiges of their passing, other than their surnames, are the forlorn ruins of their once-imposing homes and buildings, the expertly dry-laid stone walls that surrounded their fields, and the fort that once protected them.