Fort St George Expedition Log

By Donald H Keith

Yesterday marked the end of our two weeks of field work on Ft. George Cay. It was a little sad to backfill the test excavations, take down our base camp, and shuttle everything back to Pine Cay. We didn’t accomplish as much as I hoped, but there’s nothing new about that. I’ve always been suspicious that meeting all your goals may mean that they weren’t set high enough to start with.

There is still a lot of Ft. George Cay to explore. We did not set foot on every square meter of land or comb the shallows offshore as thoroughly as I intended. Clumps of really dense bush discouraged us from testing many promising areas. But we managed to accurately map the locations where we found evidence of habitation and put them on geo-registered high-resolution digital aerial photos of Ft. George Cay using a program called Oziexplorer. This is important because the part of the cay currently protected by legislation is only 1 acre. The maps now irrefutably demonstrate that structures and artifacts belonging to the fort cover at least 8 acres and probably much more.

There is still a lot of Ft. George Cay to explore. We did not set foot on every square meter of land or comb the shallows offshore as thoroughly as I intended. Clumps of really dense bush discouraged us from testing many promising areas. But we managed to accurately map the locations where we found evidence of habitation and put them on geo-registered high-resolution digital aerial photos of Ft. George Cay using a program called Oziexplorer. This is important because the part of the cay currently protected by legislation is only 1 acre. The maps now irrefutably demonstrate that structures and artifacts belonging to the fort cover at least 8 acres and probably much more.

Last night we gave a brief presentation at the Meridian Club. For us it was an honor and a privilege because many of the people who pioneered the exploration of Ft. George decades ago were in the audience. We owe them a lot; they have been the custodians of the fort for more than 30 years. They are the ones who brought Ft. George and its history to our attention, the ones who first voiced alarm at how rapidly it is eroding into the sea, and the ones who made this expedition possible. They initiated research in Great Britain and elsewhere to pick up the wispy historical threads that reveal who built the fort, when it was constructed, and why. One Pine Cay couple has already donated their collection of documents, maps, and artifacts to the Museum and another collection is pledged. A very accurate and highly detailed map of the principal ruins that they made in 1998, when compared with ours, furnishes incontrovertible evidence of the rate of erosion experienced by the part of the fort closest to shore. At least 40 feet of it has fallen into the sea in the last 11 years!

Last night we gave a brief presentation at the Meridian Club. For us it was an honor and a privilege because many of the people who pioneered the exploration of Ft. George decades ago were in the audience. We owe them a lot; they have been the custodians of the fort for more than 30 years. They are the ones who brought Ft. George and its history to our attention, the ones who first voiced alarm at how rapidly it is eroding into the sea, and the ones who made this expedition possible. They initiated research in Great Britain and elsewhere to pick up the wispy historical threads that reveal who built the fort, when it was constructed, and why. One Pine Cay couple has already donated their collection of documents, maps, and artifacts to the Museum and another collection is pledged. A very accurate and highly detailed map of the principal ruins that they made in 1998, when compared with ours, furnishes incontrovertible evidence of the rate of erosion experienced by the part of the fort closest to shore. At least 40 feet of it has fallen into the sea in the last 11 years!

Although the field work portion of our archaeological exploration of Ft. George is finished, the project is far from over. We have artifacts and samples to clean, conserve, and analyze, articles and reports to write, and exhibits to prepare. We hope that our efforts will engender a greater awareness of the historical importance of Ft. St. George, how rapidly shore erosion is destroying parts of it, and how time for efforts to protect and preserve it is running out.

Although the field work portion of our archaeological exploration of Ft. George is finished, the project is far from over. We have artifacts and samples to clean, conserve, and analyze, articles and reports to write, and exhibits to prepare. We hope that our efforts will engender a greater awareness of the historical importance of Ft. St. George, how rapidly shore erosion is destroying parts of it, and how time for efforts to protect and preserve it is running out.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Toni Carrell

We went back to the Poison Wood Area with the instruction to “. . . see if those conch shells mean anything.” Fortunately, we’d already expanded the cleared area of leaf litter and done some limited testing. Here is a list of what turned up:

We went back to the Poison Wood Area with the instruction to “. . . see if those conch shells mean anything.” Fortunately, we’d already expanded the cleared area of leaf litter and done some limited testing. Here is a list of what turned up:

2 iron eye-bolts

10 small cream ware ceramic fragments

3 small blue transfer ware ceramic fragments

2 brown slipware ceramics

1 gray slipware ceramic

2 large cast iron slabs, curved, one with a “tab” (found the day before)

2 pieces of copper alloy sheet 3 by 4 inches (one with two very small tack holes)

8 iron round- and/or square-shanked nails (in a concentrated area)

2 pipe stem fragments

2 large green glass bottle bases (and quite a few fragments)

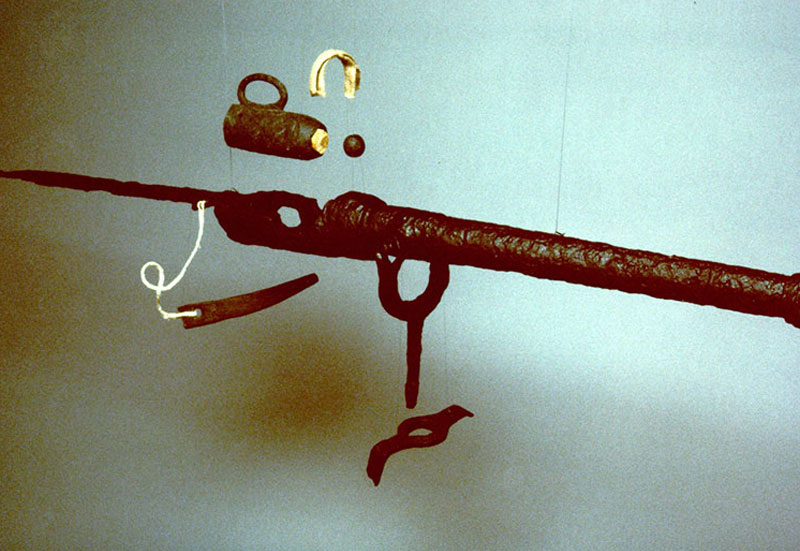

1 musket ramrod pipe fragment (see image below)

1 copper alloy object with some organic wrapping on one end

1 piece thick ceramic, rim section

1 piece stone, worked

6 buttons, two different sizes

fire brick pieces

What do YOU think this all means? Hint – can you group these into activities?

Here are a few more clues:

– This area is about 150 feet away from a clearly defined stone foundation.

– The two large cast iron slabs turned out to be quite different on closer inspection. The one with the “tab” is really the base to a Dutch oven with only one leg remaining.

– The piece of thick ceramic that is a rim section looks like part of a chamber pot.

– The piece of worked stone is actually the flint (see image below) to a musket’s firing mechanism.

If you are thinking house site, keep in mind we did not find any foundation stones here. On the other hand those curios iron eye bolts could be tent pegs or the concentration of iron nails could suggest a wooden framed building. All those soldiers had to live some where, right? But neither of those structures would leave much evidence.

If you are thinking house site, keep in mind we did not find any foundation stones here. On the other hand those curios iron eye bolts could be tent pegs or the concentration of iron nails could suggest a wooden framed building. All those soldiers had to live some where, right? But neither of those structures would leave much evidence.

The Dutch oven, conch shells, ceramics, glass bottles, and pipe stems certainly points to at least an area where they were eating, drinking, and smoking.

If you are still scratching your head, then you are not alone. But that is the biggest challenge in archaeology — to keep trying to fit the pieces together to come up with a picture of the past.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

A Guest Blog

By Dr. Charlene Kozy

Authority on the Loyalist Planters in the Turks & Caicos Islands

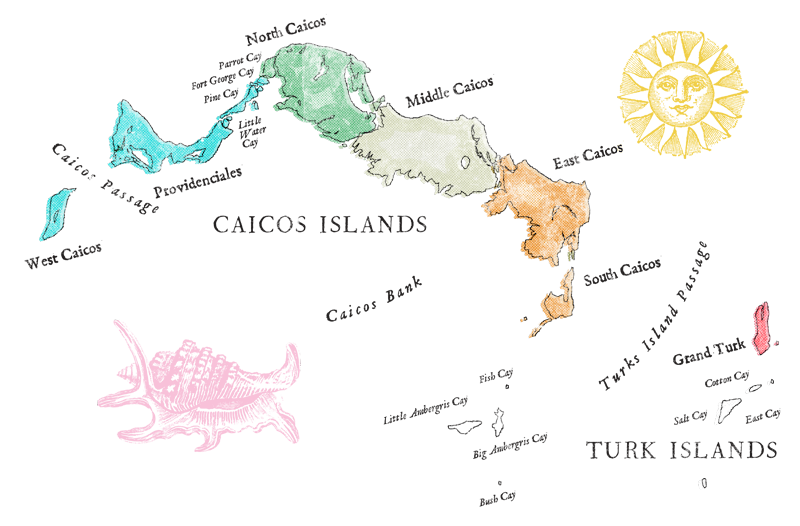

A short while ago I was asked if I knew who built Fort St. George. Without hesitation, I answered, “Thomas Brown, one of the American Loyalists that settled on the Caicos Islands.” My answer was based on original sources found in the Colonial Office in London. In one letter, written to the Earl of Camden, Brown told how he “met the threat of a French invasion in an area totally out of protection of government and is daily exposed to capture or destruction.” He states that he constructed two forts at his own expense and provided the same with 14 guns from the last war and built a furnace for the “heating of shot” (remains of furnace at left).

A short while ago I was asked if I knew who built Fort St. George. Without hesitation, I answered, “Thomas Brown, one of the American Loyalists that settled on the Caicos Islands.” My answer was based on original sources found in the Colonial Office in London. In one letter, written to the Earl of Camden, Brown told how he “met the threat of a French invasion in an area totally out of protection of government and is daily exposed to capture or destruction.” He states that he constructed two forts at his own expense and provided the same with 14 guns from the last war and built a furnace for the “heating of shot” (remains of furnace at left).

He wrote to the Under Secretary of State encouraging the British to recognize Fort St. George as an important port for trading in the Caribbean and asked that it be fortified. He retells about the construction of forts and the provisions provided by the inhabitants of the Island. (CO260/19) A third letter written to John Sullivan, Esq. describes Grand Caicos as:

“being surrounded…of rocks and shoals is, as far as my knowledge extends…fortified by nature than any island in the west. The quarter of the island most vulnerable is at St. George”s…where inhabititants for the protection of the harbor…at their own expense, constructed a stockade, a…platform for 16 guns, furnace for heating shot…barracks for 40 men. The Garrison, principally consisted of Blacks, the property furnished by the inhabitants, who did duty at Ft. George until relieved by a detachment of His Majesty’s 63 Regt…Artillery sent by Lord Balcarras from Jamaica …of Saint Domingo by the British Forces” (CO260/18).

The British began issuing land grants to Loyalists between 1789-1790. (Bahama Registry) but cotton cultivation had not gained the importance that the sugar plantations held in the West Indies . When the British and French began a war in the West Indies the Caicos was dangerously exposed and this stimulated the new settlers to try to protect their property.

Thomas Brown came to America at age 24. Seeds of the revolution had been sown and his verbal support of the King led to harsh treatment by the Sons of Liberty. He became one of the ablest fighters for the King and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the King’s Rangers Regiment. Many of the men who fought with him in America settled with him on the Caicos. He is well known in American history for his ability and resilience. He fought from forts and would understand their construction and value.

Dates would suggest that Brown and/or his followers built the fort(s) after 1793. The British sent a regiment sometime after October, 1798 led by Neil Campbell to man the fort perhaps at Brown’s request. Campbell returned to England in 1800. (The Bahama Almanac and Register for the Year 1801. Memoir of Sir Neil Campbell.)

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Toni Carrell

For the past couple of days we fanned out across the island to see if we can locate any other structures from the fort. We’ve hacked, crawled, and swatted lots of mosquitoes along the way and have learned a lot. One of the things we’ve learned is that it is likely that not all of the buildings were constructed of stone and if there are other buildings they will leave only very subtle clues.

A good example is the infamous “Poison Wood” area. Despite our concerns about going back in there, we poked around removing leaf litter and scraping away the thin topsoil. One of the first things uncovered was a concentration of old, very old, conch shells. We know from the other structures that the soldiers were eating a lot of conch. Then we saw some very tiny fragments of typical ceramics (called cream ware and blue transfer ware). A bit more investigation turned up some heavy pieces of cast iron and some iron nails.

A good example is the infamous “Poison Wood” area. Despite our concerns about going back in there, we poked around removing leaf litter and scraping away the thin topsoil. One of the first things uncovered was a concentration of old, very old, conch shells. We know from the other structures that the soldiers were eating a lot of conch. Then we saw some very tiny fragments of typical ceramics (called cream ware and blue transfer ware). A bit more investigation turned up some heavy pieces of cast iron and some iron nails.

But the question is, “Is this an area where there was a building or just where they threw stuff?”

We really want the answer, so we plan on going back there tomorrow to do some more work. Stay tuned . . . maybe we can figure this out together.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Neal Hitch

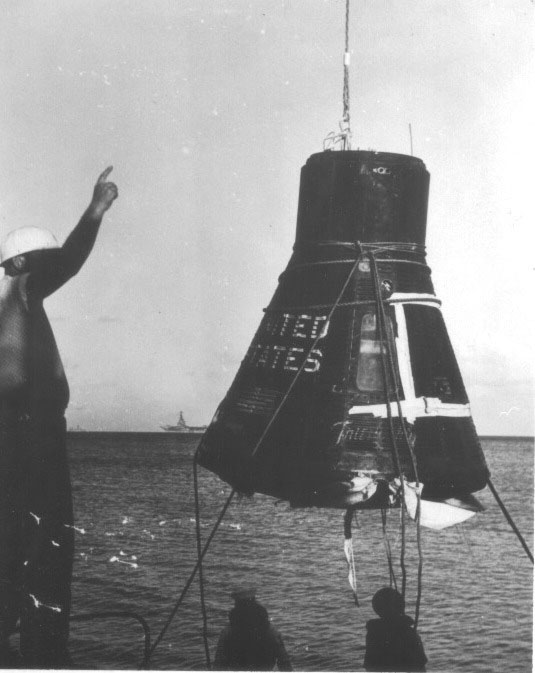

We found a cannon today.

Off of the north shore of Fort George there are cannons in the water. They are a snorkeling attraction.

Thomas Brown wrote that he outfitted the battery at Ft. George with 16 cannons in the 1790s. In 1967, the British Directorate of Overseas Survey completed an Ordnance Survey Map which located six cannons on a hand map of the cay. Three of the cannons are visible above the sand today. Five cannons were identified and measured by Dr. Donald Keith in 2008.

In July 2008, a magnetometer survey was completed around Ft. George Cay. The magnetometer is a survey instrument that records the magnetic field in a given area. It is used to locate buried iron objects. The results of the magnetometer survey included seven large magnetic anomalies on the north shore of Ft. George.

In July 2008, a magnetometer survey was completed around Ft. George Cay. The magnetometer is a survey instrument that records the magnetic field in a given area. It is used to locate buried iron objects. The results of the magnetometer survey included seven large magnetic anomalies on the north shore of Ft. George.

On the second day of the survey we located five cannons and Will Allen got some great photos of them (see image at right). At the end of last week we located cannon number six. This cannon was sitting just a few inches under the sand with the cascabel toward the sea and the muzzle toward the beach.

Today, we found cannon number seven. This cannon has never been documented at Ft. George before today. The magnetometer survey showed a large iron object located 50 yards south of the other cannons. At the end of the day we decided to do a little extra “water work” and set about trying to find the extra cannon. We found it by calculating a distance from the grids on the survey map and running a measuring tape off of the existing cannons. We marked an area at 64 meters and began to swim up and down the beach with a metal detector. About forty five minute later we hit a very large iron artifact.

The cannon sits six to eight inches under the sand, upside down, with the muzzle pointing back towards the other cannons. It is 4 foot eleven inches long. The muzzle boar diameter is 3 inches. This may have been a 4 pounder. It was an amazing find at the end of a long day. By tomorrow the cannon will have been consumed by the sand again, but now we know that it exists.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Will Allen, Volunteer

As a professional photographer I often travel to remote destinations photographing or filming whatever I can, usually sharks or some sort of underwater life. Just before I head out on a new expedition I get comments from friends back in Montreal along the lines of … “Poor you, working in an island paradise” or” Wow, it sure sucks to be you.” So when one of my best friends tells me he’s going to his place in the Turks and Caicos to do an archaeological dig on a tiny island called Fort St. George Cay and it happens to coincide with my vacation time, I jump on the chance to tag along and help out.

After a little back and forth and logistics we settle on some dates that work and the next thing I know I’m standing on Fort St. George Cay with a machete in one hand and a metal detector in the other hacking down poisonwood trees and shrubs attempting to find anything that gives us clues into the past. The people I met and the experiences I had on this trip will stay with me for a lifetime. I now have a personal attachment to this little island because my close friend is living a stones throw away from the old fort and he introduced me to it on my first visit years ago. So helping out on this, despite the threat of poisonwood and whatever else may lie hidden under the brush of Fort George, is a real opportunity. We have since found a multitude of cannon balls, shot, buttons and many more objects that give us a glimpse into the past of what life may have been like on the island.

After a little back and forth and logistics we settle on some dates that work and the next thing I know I’m standing on Fort St. George Cay with a machete in one hand and a metal detector in the other hacking down poisonwood trees and shrubs attempting to find anything that gives us clues into the past. The people I met and the experiences I had on this trip will stay with me for a lifetime. I now have a personal attachment to this little island because my close friend is living a stones throw away from the old fort and he introduced me to it on my first visit years ago. So helping out on this, despite the threat of poisonwood and whatever else may lie hidden under the brush of Fort George, is a real opportunity. We have since found a multitude of cannon balls, shot, buttons and many more objects that give us a glimpse into the past of what life may have been like on the island.

Unfortunately I only had one week to help, but will remember it for the rest of my life. I learned more than I ever thought I would from the great team of archaeologists. From photographing a couple of huge cannons that lie just off shore in a few feet of water, to digging holes in the sand to find a tiny piece of metal that could have been a nail, or perhaps a piece of a barrel loop, there have been endless adventures on Fort St George. I’m convinced that this team will make a huge difference to the island’s future and well being.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Donald Keith

Last night we visited Pine Cay home owners Jack McWilliams and his wife, Mary. They had some things they wanted us to see. Jack and I go way back. He is the one who took me to see Ft. George Cay for the first time at least 10 years ago. Jack spent a lot of time over the last couple of decades exploring the ruins and keeping a sharp eye out for artifacts that occasionally turn up on the beach or in the bush, half covered in leaves. These objects made him and other people on Pine Cay curious about the history of Ft. George. They began to make inquiries and look for old records that might reveal who built the fort and when it was occupied. Over the years this small group of friends collected artifacts and compiled a lot of important information that goes a long way toward answering these questions.

Fortunately for us, they even made carefully measured maps of the ruins on the island. These maps reveal that over the last 10 years at least 50 feet of the northwestern shore of Ft. George, where a large part of the fort was sited originally, has eroded away into the sea, taking with it most of the largest structure. Extrapolating that rate of erosion back 200 years, one can easily imagine that the cannons, now lying in chest-deep water 150 feet off shore, were once on solid land.

Fortunately for us, they even made carefully measured maps of the ruins on the island. These maps reveal that over the last 10 years at least 50 feet of the northwestern shore of Ft. George, where a large part of the fort was sited originally, has eroded away into the sea, taking with it most of the largest structure. Extrapolating that rate of erosion back 200 years, one can easily imagine that the cannons, now lying in chest-deep water 150 feet off shore, were once on solid land.

Jack came with us over to Ft. George a few days ago. His familiarity with the island was so intimate we started calling him “GPS McWilliams.” He was amazed at how much of what we call “Structure A” has disappeared since the last time he visited the island a few years ago. Pushing back into the bush we showed him two other structures that he had heard about, but never visited in person. In turn, he showed us things we had not noticed, including an area he called “the dump” where he found all sorts of artifacts jumbled together in a shallow pit.

This was the reason we visited him at his home last night. Although we have found an abundance of lead and iron shot, musket parts, iron fasteners, shards of ceramic and glass vessels and the like, the objects Jack found at “the dump” were different and more varied. One of his most remarkable finds was a fragmentary bone knife handle with the letter “M” clearly inscribed on it. He also found bone buttons and the stock from which the buttons were being cut.

This was the reason we visited him at his home last night. Although we have found an abundance of lead and iron shot, musket parts, iron fasteners, shards of ceramic and glass vessels and the like, the objects Jack found at “the dump” were different and more varied. One of his most remarkable finds was a fragmentary bone knife handle with the letter “M” clearly inscribed on it. He also found bone buttons and the stock from which the buttons were being cut.

Our hats are off to Jack and the other “Pine Cay Pioneers” who started exploration of Ft. St. George Cay decades ago, and who have shared their knowledge and enthusiasm with us, and who have made our archaeological exploration of Ft. George Cay possible.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By David Stone, Volunteer

I am writing this blog on day five of the survey from the comfort of my hotel suite in Provo. The other team members are slaving away in the hot sun while my wife and I had to take a day off and recuperate. Reality is slowly setting in and the heat and humidity are taking their toll. Not that the work is particularly arduous, in fact, it is incredibly interesting as we are learning new things almost by the minute. And it is especially gratifying and rewarding from an inner sense and perspective.

On the third day of the project, and our first in the water, I was able to see very clearly the five submerged cannons. Now this is getting exciting! I imagined troops standing behind the cannons loading them and firing them at the enemy out on the reef. If I were a button that’s where I’d fall off – right behind a cannon. And one of my hopes for this project was that I would find a button that could help to fill in the story of the fort and its soldiers.

One of the more common items we are finding on land and in the water are pieces of shot, bits of iron and other metal fragments, often concreted together. So when my detector beeped yet again behind one of the partially buried cannons it was nothing special. I figured it was probably just another chunk of shot.

For some unexplained reason I happened to look in my sand scoop. Caught between the two screens I spied what I thought was a nickel. It was about the right size but appeared a bit curved and devoid of any writing. Closer examination revealed I had found my button! Neal Hitch told me that only a few of these buttons were found previously, but only on land. The ocean has taken its toll on this button and a bit of the detail is worn off from being submerged for some 200 years.

For some unexplained reason I happened to look in my sand scoop. Caught between the two screens I spied what I thought was a nickel. It was about the right size but appeared a bit curved and devoid of any writing. Closer examination revealed I had found my button! Neal Hitch told me that only a few of these buttons were found previously, but only on land. The ocean has taken its toll on this button and a bit of the detail is worn off from being submerged for some 200 years.

That afternoon back at Pine Cay, Neal and I found a British website with over 100 British regimental uniform buttons on display. The new button matched one on the website perfectly, although not in as good a condition and it is dated 1795. He pointed out that we don’t know what that means exactly. Was the button made only in 1795? Was the first appearance of the button in 1795 and how long was it made? A few answers and lots more questions. But from now on I can say that the best button from Ft St George was found under what is — in my opinion — the best cannon.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Elizabeth Stone, Volunteer

Day 1

Today we went out to the Cay and met our fellow adventurists…a really fascinating bunch from all over…3 Phd’s, a professional underwater photographer, a doctor, a couple of year-rounders, and, of course, us. Armed with machetes, metal detectors, saws and the like…today’s focus was on clearing brush around the remnants of a visible structure and looking for artifacts that might indicate its purpose.

Today we went out to the Cay and met our fellow adventurists…a really fascinating bunch from all over…3 Phd’s, a professional underwater photographer, a doctor, a couple of year-rounders, and, of course, us. Armed with machetes, metal detectors, saws and the like…today’s focus was on clearing brush around the remnants of a visible structure and looking for artifacts that might indicate its purpose.

We did find some shot, pottery shards, some pieces from a musket, and mapped out the original footprint of one of the buildings. My time was spent doing field photography … shooting people doing whatever they were doing as well as amateur photos of what we found. It was sunny, HOT and buggy (no surprise). There were tons of hermit crabs scuttling everywhere…probably wondering what all the commotion was about…and fire ants (yikes!), that we managed to avoid. This is going to be a LOT of fun. I love meeting new people and, of course, anyone who is interested in history. Funnily enough, the head of the project does sort of look like Indiana Jones.

The thing that amazes me is the resilience of the soldiers who were stationed here. These Cays are scrubby (not much shade) and I can only imagine their reaction, being dumped here. How did they get water? How did they spend their days? What tools did they have to construct these structures? The boredom, bugs, inhospitable environment, and unrelenting sun….just fires my imagination….and certainly elicits my sympathy. Early to bed tonight because 5:30 a.m. is going to come too quickly. I’m blessing air conditioning right now and the thought of soft sheets…I wouldn’t have made a very good colonist.

Day 4

Every day that we are out on the Cay, I compare the obstacles that we face with what the soldiers faced 200 years ago. While we brought coolers with food and water, metal detectors and machetes, compasses and protractors, cell phones and walkie-talkies, bug spray and sunscreen, the soldiers must have carried little more than basic tools with which to construct buildings, hard tack, water collection implements, and clothing. But, being English, they also brought dishes and even teacups, according to our finds! While we have cold water on hand, they had to fetch it and it was never better than tepid. There is little wildlife on island, so any food they ate, had to come from the sea, the air, or what they grew. When I compare their fortitude and dedication to ours, I feel that we come up short. They too had to hack through the brush as we are doing…but their intent was to build living quarters and fortifications, while ours is to merely uncover those endeavors. The brush that thwarts them also thwarts us.

Yet in my view, we don’t always come up short. In watching Don, Neal and Toni I am amazed at their fortitude and dedication and, yes, reverence and respect, for what we are discovering. They are patient and methodical often seeing a small artifact that is camouflaged by the overgrowth that I would have missed entirely. And when the sun goes down, when the soldiers would have been sleeping, our team is at their maps and computers: measuring, documenting, sourcing and referencing the finds. So our modern perseverance and diligence is of a different variety and no less impressive.

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

By Toni Carrell, Ships of Discovery

I discovered early in my career that archaeologists have this love-hate relationship with artifacts. Or at least I have a love-hate relationship with them. It would be so much fun to just go out and dig up “stuff” and then go back to camp and take a shower and enjoy the evening with a cool drink. But nooooo.

Hold that thought.

If you’ve been reading the blogs you will know by now that we are dividing the work up into several different tasks. The first task, and one that is ongoing, was to clear away the bush around the known structures on Ft St George Cay. For the most part all of them were found (and even measured) by the true pioneer explorers of the island: Brooke Foxe, Jack McWilliams, Walt Brewer, Terry Smith and Lee Smith. In the process we are cutting branches, raking leaf cover, snipping roots, and generally getting hot, sweaty, mosquito bitten and really dirty.

The second task is to connect the various structures – so far we have three distinct locales and a fourth possible. To do that we have cut what Robert calls “elephant trails” between them. Our elephants are of the miniature variety and the trail is more a track, but that is another story. Randy, Will, and Robert have been doing a stellar job on that score.

The third task is to go out and locate previously unknown structures. That is how Neal managed to get into the Poison Wood. We are starting a bigger push on that task tomorrow.

The fourth task is to clean up the exposed structures and to begin their documentation. That is where I come in. My job is to draw and measure. But in the process of cleaning up the leaf litter and then exposing the foundations, invariably artifacts show up. Randy already mentioned the musket furniture we found. When we find anything, we immediately put in a pin flag – a thin plastic stick with an orange flag. We’ve been very surprised at how many small finds have surfaced in this process.

The fourth task is to clean up the exposed structures and to begin their documentation. That is where I come in. My job is to draw and measure. But in the process of cleaning up the leaf litter and then exposing the foundations, invariably artifacts show up. Randy already mentioned the musket furniture we found. When we find anything, we immediately put in a pin flag – a thin plastic stick with an orange flag. We’ve been very surprised at how many small finds have surfaced in this process.

And here is where my love-hate relationship with artifacts comes in. Each of these artifacts, the ones that are diagnostic (that is, will tell us something important) and even those that are not (but will give us an idea of general activity areas) must be recorded. Not just photographed, but their exact location noted. This entails taking measurements from each find to a baseline or other known point. You can think about it almost like a spider web – with all of the lines radiating out from the center to the artifacts at the ends and then connecting to the centers of other spider webs. Each artifact that is collected also gets a number and a little plastic tag so that it can be cross-referenced to the list of measurements.

Other team members are finding artifacts, not just me. So at the end of the day, or whenever I can pry them away from bushwhacking and exploring, I am tracking them down and making sure I can find all of their pin flags. Then Elizabeth and I crawl around on our hands and knees through the bush to get the measurements before the mosquitoes eat us alive or we inhale one that gets too close. When that happens I am reminded that, “The trouble with archaeology is . . . the artifacts!”

Other team members are finding artifacts, not just me. So at the end of the day, or whenever I can pry them away from bushwhacking and exploring, I am tracking them down and making sure I can find all of their pin flags. Then Elizabeth and I crawl around on our hands and knees through the bush to get the measurements before the mosquitoes eat us alive or we inhale one that gets too close. When that happens I am reminded that, “The trouble with archaeology is . . . the artifacts!”

- Published in 2009 Expedition Log

- 1

- 2