The First People in Turks & Caicos

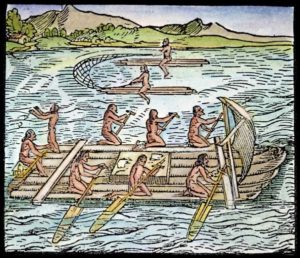

Eight hundred years before Columbus arrived in the Bahamian archipelago, Native American peoples thrived on these islands.

Lucayan History

The Lucayans (pronounced lu-KIE-an) were the original inhabitants of the Bahamas archipelago before the arrival of Europeans. They were a branch of the Taínos who inhabited most of the Caribbean islands.

The Lucayans (pronounced lu-KIE-an) were the original inhabitants of the Bahamas archipelago before the arrival of Europeans. They were a branch of the Taínos who inhabited most of the Caribbean islands.

Originating in South America, these Indians spread northward along the arc of the Windward Islands, passing to the Leewards, then west to the Greater Antilles, and finally north to the Bahamas chain. They spoke the Taíno language, one of the Arawakan languages.

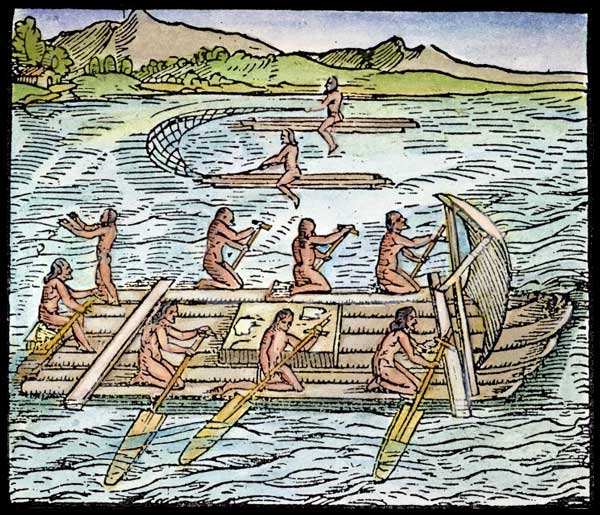

The highly developed Lucayan culture boasted its own language, government, religion, craft traditions, and extensive trade routes. Christopher Columbus’s diario is the only source of first-hand observations of the Lucayans. Other information about the customs of the Lucayans has come from archaeological investigations and comparison with what is known of Taino culture in Cuba and Hispaniola. The Lucayans were distinguished from the Tainos of Cuba and Hispaniola in the size of their houses, the organization and location of their villages, the resources they used, and the materials used in their pottery (Keegan 1992; Craton 1986).

From an initial colonization of Great Inagua Island, the Lucayans expanded throughout the Bahamas Islands in some 800 years (c. 700 – c. 1500), growing to a population of about 40,000. Population density at the time of first European contact was highest in the south central area of the Bahamas, declining towards the north, reflecting the progressively shorter time of occupation of the northern islands. Known Lucayan settlement sites are confined to the nineteen largest islands in the archipelago, or to smaller cays located less than one km. from those islands. Keegan posits a north-ward migration route from Great Inagua Island to Acklins and Crooked Islands, then on to Long Island. From Long Island expansion is thought to have gone east to Rum Cay and San Salvador Island, north to Cat Island and west to Great and Little Exuma Islands. From Cat Island the expansion proceeded to Eleuthera, from which New Providence and Andros to the west and Great and Little Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama to the north were reached. Lucayan village sites are also known on Mayaguana, east of Acklins Island, and Samana Cay, north of Acklins.

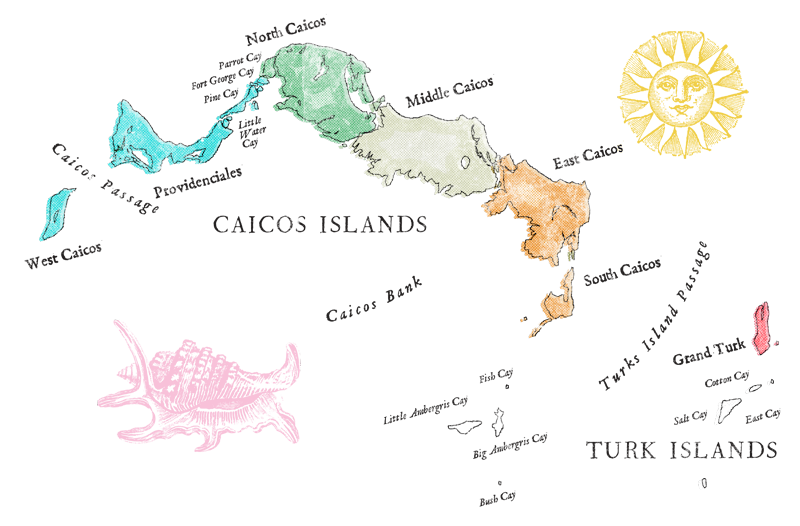

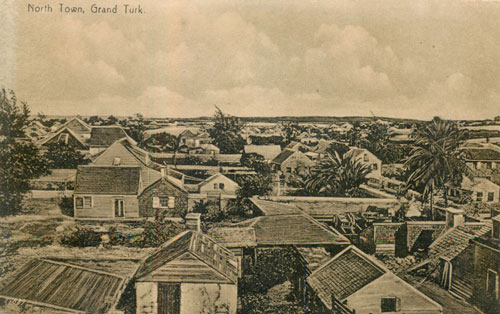

In the Turks and Caicos Islands, there are village sites on West, East, Middle and North Caicos, on Providenciales, and on Grand Turk, at least some of which Keegan attributes to a later settlement wave from Hispaniola. Population density in the southern-most Bahamas remained lower, probably due to the drier climate there (less than 800 mm of rain a year on Great Inagua Island and the Turks and Caicos Islands and only slightly higher on Acklins and Crooked Islands and Mayaguana) (Keegan 1992).

Based on Lucayan names for the islands, Granberry & Vescelius argue for two origins of colonization; one from Hispaniola to the Turks and Caicos Islands through Mayaguana and Acklins and Crooked Islands to Long Island and the Great and Little Exuma Islands, and another from Cuba through Great Inagua Island, Little Inagua Island and Ragged Island to Long Island and the Exumas. Granberry & Vescelius (2004) also state that around 1200 the Turks and Caicos Islands were resettled from Hispaniola and were thereafter part of the Classical Taino culture and language area, and no longer Lucayan.

Unfortunately, the Lucayan culture was technologically unsophisticated when compared to European society. So when the Spaniards arrived, they quickly conquered these peaceful people. Using the Lucayans as miners and pearl-divers in a de facto slave system, the new arrivals worked many of them death. Others were killed outright for sport. Still others committed suicide or died from acute depression. Many died from European diseases for which they had no immunity. Within a single generation of Columbus’s landing, the Turks and Caicos Islands were stripped of their population. Few written records of this civilization ever existed. Consequently, archaeology is our most important tool in studying these extinct people.

Archaeology of the Lucayans in the Caicos Islands

In the mid 1970s, anthropologist Shaun Sullivan conducted a pioneering survey of Middle Caicos. He found remains of a ball court, an indication of substantial and sophisticated long term habitation. Following up on Sullivan’s work, Dr. William Keegan at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, Florida, has excavated in the Turks and Caicos Islands for more than two decades. His excavation of a site on Grand Turk revealed the earliest known settlement in the Bahamian chain.

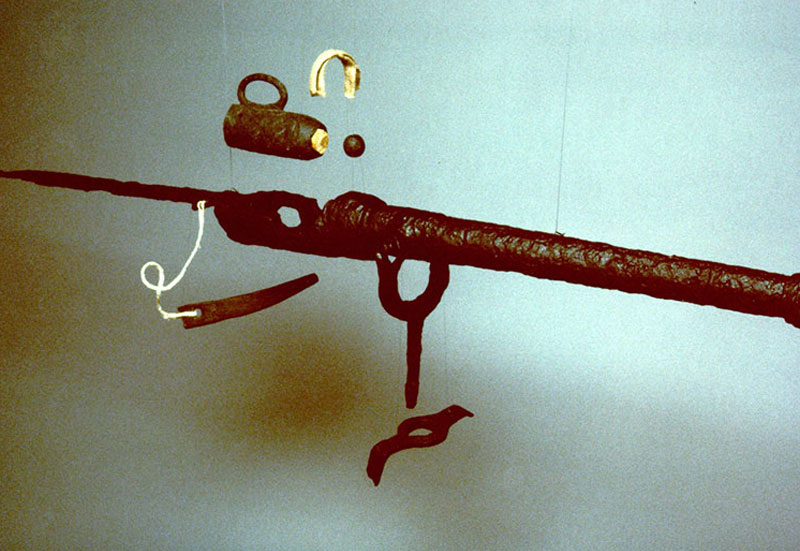

Lucayan paddle found on Grand Turk

In 1996, Captain Bob Gascoine was working in a mangrove swamp at North Creek on Grand Turk. Suddenly his propeller struck a submerged object. Curious, the Captain investigated the sound and found he had run over an odd reddish stick poking out the mud. An amateur archaeologist, Gascoine recognized that this was not stick but a Lucayan canoe paddle. He hastily summoned the Museum and the paddle was removed to a stable environment.

The only other such existing paddle was found in the Bahamas in 1912. The paddle originally went to the Heye Museum in New York. The Heye collected only American Indian artifacts. In the last few years the Smithsonian has absorbed the Heye and that collection will be the nucleus of a new branch of the Smithsonian, the Museum of the American Indian. The paddle found on Grand Turk has been dated to between AD 995 and 1235. It completed conservation in Ship’s of Discovery’s Texas lab and is installed in a special exhibit at the Turks & Caicos National Museum.

Further reading on Lucayan Tainos:

- For a picture of the only other Lucayan Taino canoe paddle ever found (now housed at the Smithsonian), see: “Clues to Lucayans History on Samana” in National Geographic, November 1996 (Vol. 170, No. 5).

- The People who Discovered Columbus by William Keegan. University of Florida Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8130-1137-X

- Columbus and the Golden World of the Island Arawarks by D. J. R. Walker. Ian Randle Publishers, Kingston, Jamaica, 1992.

- Pre-Columbian Archaeology of the Turks and Caicos Islands by William F. Keegan, Caribbean Archaeology, Florida Museum of Natural History

- A History of the Bahamas by Michael Craton, San Salvador Press, 1986. ISBN 0-9692568-0-9

- Languages of the Pre-Columbian Antilles by Julian Granberry and Gary S. Vescelius. The University of Alabama Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8173-5123-X