The slave ship Trouvadore is a story of two negative incidents, both of which on their own would generally lead to tales of horror and sadness. The first was the capture and transportation of a group of Africans into slavery, a horrific journey across the Atlantic with the slave market waiting, with unimaginable horrors that work in the sugar plantations would bring. The second was the wrecking of a ship, often the tale of loss of life and the terrors as the ship succumbs and sinks below the waves.

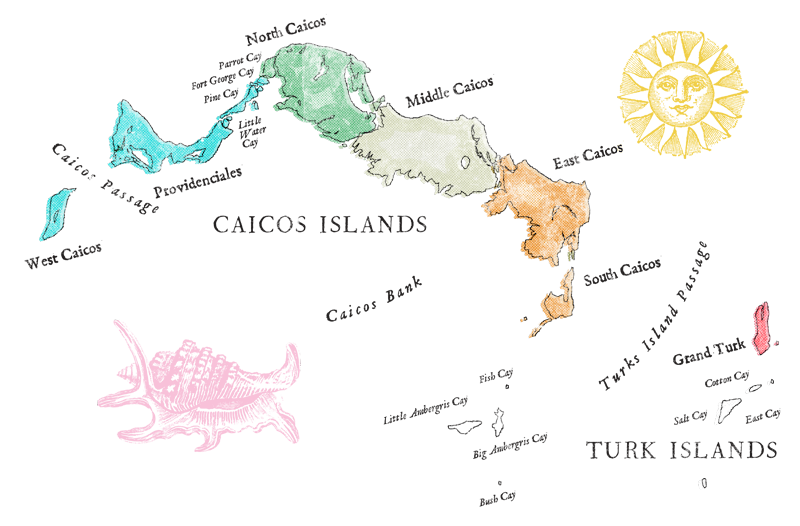

However, in this instance the two negatives mix to become a positive. The wrecking of the ship was to be the saving of 192 Africans bound for the Cuban slave markets. There fortuitous wrecking deposited the human cargo on the shores of East Caicos, in the Turks and Caicos Islands, a British Colony that had emancipated its slaves in 1834, seven years prior to the wrecking of the Trouvadore. At the same time the story of the Trouvadore is put into the context of the illegal slave trade, Liberated Africans and the period of economic change following Emancipation in this Crown Colony.

Background

In the early days the Museum looked at the Trouvadore in national terms. However, it became apparent that it would also provide an important insight into what was happening in this transitional period from slavery to emancipation in the Americas — a little covered period. Through a collaborative process involving researchers in 8 countries, family historians, cultural historians, university lecturers, scientists, archaeologists, documentary makers and publishers the story has been uncovered.

The Start of the Trail

During a search by Grethe Seim and Dr Donald Keith for Lucayan material held in collections overseas they came across letters referring to items donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, by George Gibbs, a 19th century resident of Grand Turk. One letter sent to Henry Joseph, Secretary of the Smithsonian was dated April 1878 and recorded that:

Two African idols, found on board the last Spanish slaver, of wood with glass eyes [schr Esperenza] wrecked in the year 1841 at Breezy Point on the Caicos Islands. The slaves from this vessel were taken possession of by the Government and brought to the Grand Turk Island. The captain of the slaver, escaped the penalty, (by being a Spaniard), of being hung according to the British laws. The slaves were apprenticed for the space of one year and they and their descendants form at the present time, viz the year1878 the pith of our present labouring population.

This story of the idols, which were in fact from Easter Island, sparked an interest that started to shed light on a story long forgotten. Researchers were commissioned to find references to this sunken slaver at the Public Record Office, London, and soon the story emerged.

The Trouvadore – The Story

The Wrecking and Rescue

The ship that sank in 1841 was in fact the Trouvadore and not the Esperenza. Gibbs had confused two slavers that wrecked off the Caicos Bank: the Esperenza wrecked in 1837 (see the Winter 2003/2004 Astrolabe).

The Trouvadore was a brigantine sailing under Spanish papers from Santiago, Cuba. The crew were Spanish but during the crossing to Africa some died and were replaced by Portuguese sailors picked up on Sao Tomē, an island off the west coast of Africa. No records have been found to confirm where the slaves were loaded, or how many. As the ship docked at Sao Tomē they would have been collected there or nearby on the West Coast of Africa: it would not have hung around risking capture by the British Navy. Fortunately for the Africans, after a month at sea travelling to Cuba the ship wrecked on the Caicos Bank, saving them from a life of slavery.

The ship was carrying 20 crew and 193 Africans when it sank but soon after landing one African was shot dead. One of the first locals on the scene, Mr Stevenson, was offered $3000 by the Spanish captain to obtain a vessel to take the crew and slaves onto Cuba. Mr Stevenson, who had also helped in the rescue of Africans from the Esperenza in 1837, delayed the Captain enough so that the authorities in Grand Turk could dispatch two ships and a detachment of 17 soldiers to pick up the survivors.

Distribution of the Liberated Africans

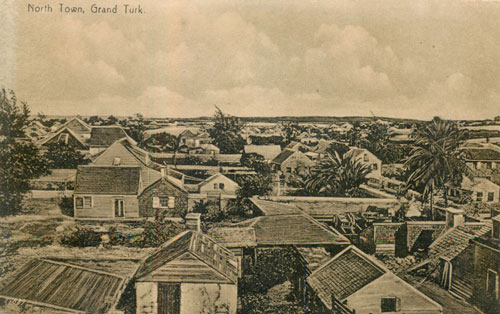

Once collected the survivors were taken to Grand Turk where the ship’s crew were imprisoned in the upper room of the old court house and the Africans were placed inside the crowded prison. A better long-term solution was needed. Should they be returned to Africa, sent to Nassau for the Bahamas government to deal with or released into the local community?

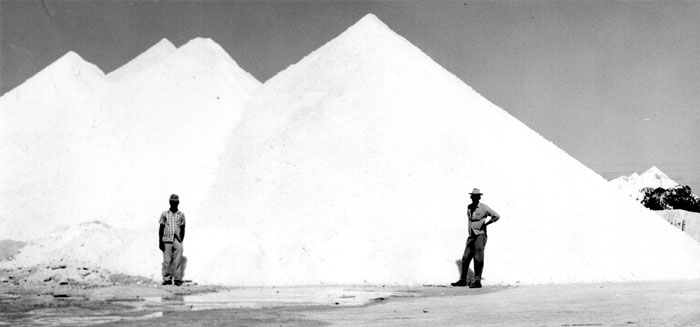

The last option was preferred but the authorities needed to recover their costs of rescuing the Africans. They also needed the support of the salt proprietors, so a compromise was reached. Of the 192 Africans, 168 were distributed amongst salt pond owners on Salt Cay and Grand Turk on a one-year contract. The 89 men, 26 women, 39 boys, 11 girls and 3 infants were given clothing, food, accommodation and medical care in return for their labour. The established church was to teach them to speak English and Christian ways, including being christened and attending services.

24 Africans, 20 men and 4 women, could not be absorbed into the local community and were taken to Nassau along with the slaver’s crew. At Nassau the crew of the Trouvadore were released into the custody of the Spanish Consul who took them to Cuba for trial, but the fate of the 24 Liberated Africans is uncertain.

In the Turks Islands, the only work was salt production. Working conditions had improved since emancipation but it was still a hard, unrewarding job and for this reason the salt proprietors were eager to take in the liberated Africans as cheap labour.

1842 and onwards – A Move to the Caicos Bank?

Did the Africans find the compassion that some suggest, or were the local population just frustrated at having new unwelcome guests and wanted to get rid of them? This question may be resolved when research identifies their final destination after 1842.

The headright system in the Turks Islands gave all British citizens an equal share of the salt ponds. It worked well for the proprietors when slave’s shares went to their owners, but now the freed slaves were on equal footing. Wealthier whites, concerned their privileged way of life was threatened, lobbied to replace headright with a leasehold system. It was during this period that the Trouvadore wrecked. This influx of Africans would have weakened the former slave owners’ rights even further. They would have accepted them as cheap labour but at the end of that year they could have been entitled to a share in the salt ponds. This would be unacceptable to the white population who would have seen sending them to the less populated Caicos Islands as the best solution. Also as the black population increased and gained positions in the community, the social order of pre-1834 was threatened.

The British Government did have certain ideas about how to treat recaptives. They were aware of the issues surrounding the arrival of so many first generation Africans into small communities and for this reason tried to keep them together. In the Bahamas they set up separate settlements where their own communities could develop but there are no records of any of these for the Turks and Caicos Islands.

Most of the population produced salt in the Turks Islands, which are low lying with little rainfall limiting the amount of freshwater and food that could be produced, making living there difficult even at the best of time. On the other hand the Caicos bank was greener and more fertile and able to sustain a population who was willing to lead a subsistence way of life. If the liberated Africans went to the Caicos Islands where would they have settled? There are only two possibilities: Middle Caicos and South Caicos

Middle Caicos

One historian recorded that Bambarra, Middle Caicos, was settled in 1842 by survivors from the wrecked slaver Gambia. However, 1842 records show that only 168 liberated Africans had settled in the Turks and Caicos Islands in the previous three years, this being the number from the Trouvadore. There is no evidence of liberated Africans from another ship landing here in this period, nor any records for a ship called Gambia being captured by the British Navy or wrecked in the Bahamian Archipelago for the years 1807 to 1860. Is this just confusing the ships name and the origins of the Africans?

Bambarra is the only settlement in the country with an African name, suggesting strong links with first generation Africans, making a good case for a link to the liberated Africans from the Trouvadore. This circumstantial evidence makes a good argument but proof is still sought. Local folklore gives Bambarra two origins. The first is that slaves owned by William Forbes settled here, accounting for why the surname Forbes is common. The second is they are descendants of Africans from a wrecked slaver. It is likely that both stories could have some basis in truth.

South Caicos

In 1842 salt production began in earnest on South Caicos. This development occurred at the right time to provide employment to the liberated Africans from the Trouvadore. Further expansion occurred after 1848 and it is likely that as salt production developed on South Caicos it would have attracted workers not only from the Turks islands but also the Caicos Islands. This development would have suited the liberated Africans from the Trouvadore; they had experience working in the salt ponds so would have been some of the earliest people to seek work in the newly developed ponds, and if they had been moved to Middle Caicos it might have only been temporary.

In 1843 the Bahamas government recorded the Turks and Caicos population as 2495. If all 168 liberated Africans from the Trouvadore had survived until 1843 they would have made up 6.7% of the population. The Turks Islands had equal numbers of men and women, whilst the Caicos Islands had a large difference. Was this due to single men going to the Caicos Islands in search of work, or was it because the liberated Africans from the Trouvadore had been moved there taking their unequal numbers with them?

Folklore and the remnants of African Society – The Cultural Links

What evidence is there to tie the liberated Africans from the Trouvadore, to today’s population and their cultural identity? These first generation Africans entered a community divided between those who had been slave owners, and those who had been slaves. The former slaves were also divided between those brought to the Islands by the Loyalists, the salt rakers and those born on the Islands. This creates a web of cultural influences and it is this rich tapestry that forms the basis of modern day customs of the “Belongers”, the name adopted by the local Islanders.

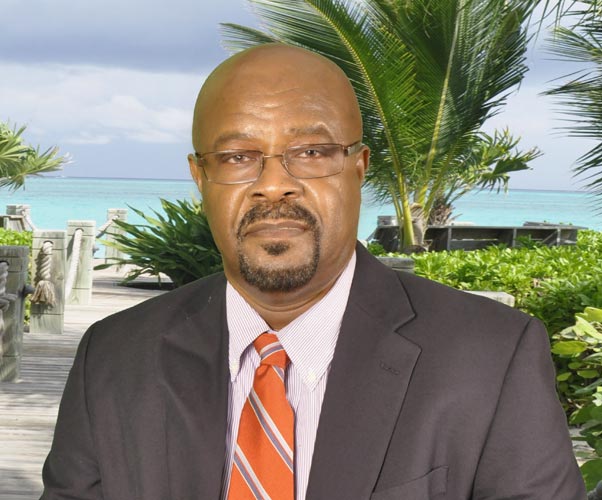

Storytelling allows the history to be passed orally from generation to generation. It is through this that one will be able to try and tie families and individuals to their ancestors who might have come from the Trouvadore. The Museum has been working closely with David Bowen, Cultural Director, who is trying to instil national pride in the Turks and Caicos Islands’ culture through music, dress, language, songs and storytelling. He also has a personal interest in the story as one of his distant relatives allegedly came from a wrecked slave ship, and lived at Bambarra.

Local crafts and arts are used as an indicator of people’s cultural background. Maybe it is just a coincidence, but the remaining straw workers are based in Middle and North Caicos. It is likely that as development has not overrun these Islands local skills and crafts which have their origins in African society, have survived. Maybe the fact that the modern Caicos Island residents are closer related to first generation Africans is also a reason. We must remember that straw work was carried out from the earliest days of slavery as the workers needed hats to protect their heads and baskets for storage. What needs further study is how the baskets are made as different styles could be linked back to Africa, and even to particular regions. Or have the baskets developed their own identity and style? This may seem to be grasping at straws but in 1891 a writer observed that in the Bahamas, liberated Africans had brought with them the secret of making African thatch for roofing houses and as they did not share their knowledge this thatch only appeared in areas settled by liberated Africans.

Another important aspect of any culture is music and means of celebration. Ripsaw, the local style of music, has a beat which is clearly African influenced. A typical celebration is Junkanoo and like the music evolved during the days of slavery but did the Africans from the Trouvadore add anything to them?

The Next Step

An important element of this story is going to be tying the local culture to its African roots through studying oral traditions and local crafts, as well as using modern scientific aids such as DNA sampling.

However, the most important step will be to look for any remains of the Trouvadore. This archaeological search and hopeful recovery of any remains will provide a tangible asset which will make it easier to tell the story in a museum display (it is planned that the Trouvadore story becomes the pivotal exhibition in a new Museum on Providenciales) and easier to prepare a travelling exhibition to go to all the countries that have assisted the research process or are linked to the Trouvadore.

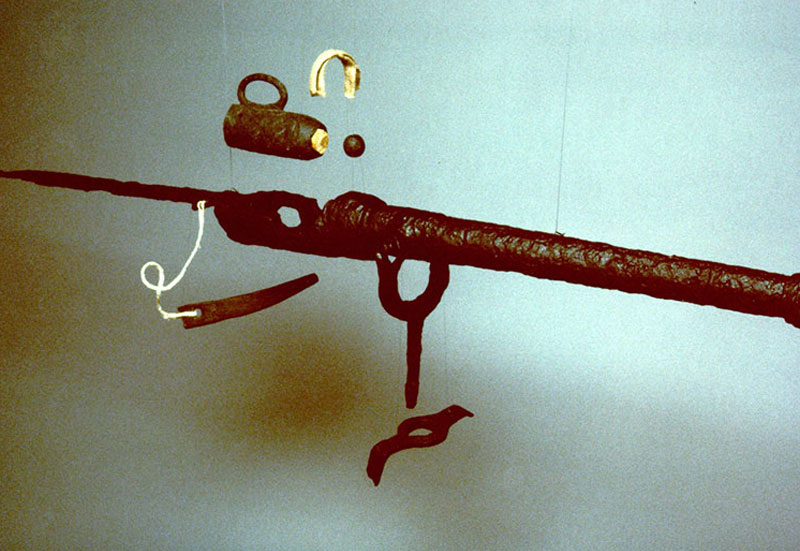

One question raised was what is left of the ship? Research indicates that extensive salvage was undertaken in 1841, hardly surprising as the locals had grown up as “wreckers”. The salvaged items, including sails, rigging and chain cables, were sold for £71.3.5, suggesting much of the ship may have been recovered.

In 2003 the Museum put in a request for a survey licence as the starting point for the search for the wreck. It is hoped that past and more recent treasure hunters have not disturbed the area destroying information that this important wreck could hold.

Conclusion

The Project will provide information to the local population, most of who are tied by blood or marriage to the survivors from the Trouvadore. We may not be able to identify any cultural activity directly to the survivors, but the Museum and Cultural Director David Bowen will increase awareness to the Islands culture, which is heavily influenced by its African roots, whether they came here as slaves or from shipwrecks. These strong cultural roots should be celebrated and not ignored or replaced by a homogenised Caribbean and/or American culture. The Museum will also portray these ties to a wider audience and it is likely a TV documentary and book will follow, increasing the availability of the research to a wider audience.