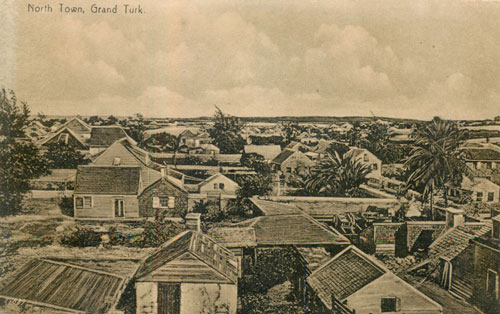

Throughout the Turks and Caicos Islands the windward beaches can be found strewn with a vast array of debris washed ashore. On Grand Turk the eastern beach is often littered with rubbish that has been deliberately thrown into the sea or washed overboard as well as a wide range of natural products such as tree trunks and coconuts. When Nils and Grethe Seim set up home on Grand Turk, Grethe enjoyed walking along the beach below her house and it wasn’t long before she found her first message in a bottle.

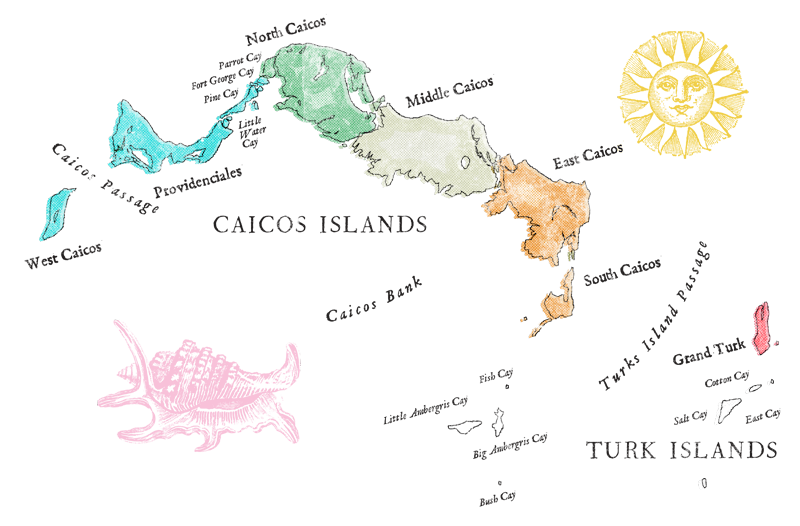

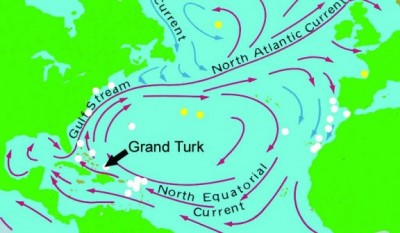

Atlantic Map with location of bottle drops in small white dots.

It was just like Grethe to become fascinated by these letters and to methodically process them. Eventually, friends assisted Grethe in her hobby by giving her messages they found in the Turks and Caicos Islands. The first task Grethe had to undertake was the removal of the letter from the bottle: not as easy as it sounds. Even if the bottle has remained watertight, after being in the sun for a long time the paper would dry out and become brittle. Alternatively, water had entered the bottle leaving the message wet. In either case, pulling the letter out of the stem of the bottle would damage it. Grethe quickly realized that the bottle was just the vessel and had to be sacrificed to retrieve the message in its best-preserved state.

Next the letter had to be deciphered. Grethe could speak several languages, which helped, but even so some letters were very difficult, either because of the language or the ink had faded. (For potential “message in a bottle” writers please see the section on how to write a message to increase the chances of the message being read.) Once a message was deciphered a response had to be drawn up. This would depend on if the letter contained a full address and the level of response depended on what the sender said in their message: I don’t think the writer of the message requesting a fiancé ever got the reply he wanted!

Where were they from?

Bottles found in the Turks and Caicos have been dropped at many locations. These include Ambrose Light, New York (which took just under 6 years to reach Grand Turk), Bimini Island, Bahamas, two from the Canary Islands (14 months for one, 27 months for another), 300 miles north of Caracas, Bermuda (2 months), Peru, West Croix, Gibraltar (5 months), Puerto Rico (2 months), Jewel Island in Casco Bay, Maine, USA (18 months), off St Thomas (one month), 150 miles west of Lisbon (16 months), Bay of Biscay (16 months), Madeira (11 months), 300 miles south east of Miami (2 weeks), between Greenland and Labrador (31 months) and 35 miles off Grand Turk (6 days).

Why are they sent?

There is a wide range of reasons why the messages have been sent: curiosity of the sender to see where it would end up: from a homesick or bored sailor: as an attempt to find a pen pal: as part of a scientific study. In fact messages can be broken down into 5 categories.

1) Accidental

Believe it or not some items are accidentally lost. Grethe included items that were not true messages in a bottle but gave enough information so that the person who lost the item could be contacted for more information. The best two examples that fall into this category are a film canister and a football. In March 1985 a film canister was found with Harriett Corbett’s name and address and when replied to it turned out that she had been on Grand Turk carrying out research. She had lost one of her films, but unfortunately it was not in the canister. One oddity here is that Harriett stated she wasn’t in the practice of putting her name into film canisters and was at a loss at how a handwritten note of her name and address ended up in the canister.

One of the most interesting though has to be the football (or to the Americans reading this a soccer ball) washed up on the east shore of Grand Turk, found on January 28, 1975. This football had the English first division teams for 1972-73 printed on it as well as “John-Philipp Wolf, Bermuda if lost send to” written in ink. After making contact in Bermuda a letter was received from John-Philipp’s father (John-Phillipp being only 7) who wrote that the ball had been lost out of the family swimming pool in November 1974. The story gained extensive coverage in the Mid-Ocean News, published in Hamilton, Bermuda, March 1, 1975 and included a picture of John-Phillip holding a football and pointing out to sea.

As well as the individuals, companies sometimes lose material overboard. This has included spare parts dropped from a container ship when the container went up in flames; one box remained in tact and floated here. Today, during the environmental clean ups any item that carries identifying marks is recorded so that investigations can take place if necessary, and maybe contact made with the relevant company or ship to find out why the rubbish is being dropped into the sea.

2) Pen Pals

Probably the greatest numbers are requests for a pen friend. These offer limited information as they often just include the name and address of the sender rather than the location or date the bottle was dropped. Some are sent by children who quickly lose interest, forget they had sent it or have inadequately sealed the bottle so the message is waterlogged and cannot be read. Some are sent by adults, including one found by Grethe that was from a man who was looking for a fiancé.

I would also include here the occasional religious message. In most cases they would request that you reply to the note and then you would be sent something on the teachings or beliefs being promoted. Grethe found one of these in February 1973. It was dropped in the sea off the coast of the Canary Islands in November 1971 and promoted Baha’ u’llah, which means the glory of God, and the laws essential for permanent peace. A return message would bring a free pamphlet on the teachings.

3) Boredom at Sea

Believe it or not many people at sea find it boring. Either they are working and the fish aren’t biting or they are on a cruise and the weather is bad. The monotony of a working person at sea can be enough to drive many to the edge of their sanity. There are many ways that they try to alleviate this boredom, and some choose to write. Many will use the conventional mail; an envelope and stamp, but some are more adventurous.

These are often the best to respond to and get responses from. The senders often put essential details in the letter: Date, rough (or even exact) location, name and address as well as other useful information such as weather, sea conditions and the ship’s name.

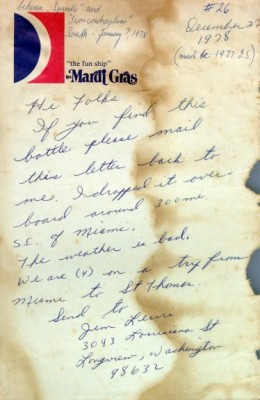

Letter 26 from the cruise ship Mardi Gras.

Letter number 26 in Grethe Seim’s collection is a good example. Written on the cruise ship Mardi Gras letterhead, Jim Lewis appears to have been bored by the bad weather. He dropped the message into the sea 300 miles south east of Miami. When Grethe found it the detective story starts. First, she found it on East Beach, Grand Turk, on the January, 7, 1978. This did not tie in with the date on the letter of December 27, 1978. So Grethe replied to the address of the sender on the January 24, 1978 just to record that she had found the bottle and to question the date on the letter. She also recorded that the latter had undergone water damage even during its short stay in the sea. This was the start of several correspondences that lasted for 20 years.

Message 48 in Grethe’s collection was from Christine Wilson, wife of the Radio operator on board the British cargo Passenger RMS St Helena, who would drop messages into the sea on her annual trip with her husband. When Grethe replied to the letter she received a photograph and brochure for the ship and a copy of the message, which included the position where the bottle entered the sea. A coincidence here was that the Wilson’s and Seim’s knew some of the same people who were linked to the Island of St Helena, including Geoffrey Guy who was a former administrator for the Turks and Caicos Islands and who had initially been booked on the RMS St Helena for this journey but had cancelled at the last moment.

4) Adventure

Some people see it as an adventure. Letting the bottle go to places they are unlikely to visit, and hopefully getting a response, much like having a friend go on holiday and sending you a postcard.

For some it is also a way to continue the adventure of a holiday. Imagine being away from work, relaxing on a cruise ship. The trip is drawing to its inevitable end and the humdrum working life back in a congested smogged-filled city is on the horizon. In an attempt to continue the break, albeit in a very abstract way, by putting a message in a bottle the holiday will continue, and if lucky the bottle will be found and responded too. When the response is received it will bring back memories of the vacation.

In this category one could include the messages dropped from Florence Rollins who had written her message on the reverse side of a cruise ship menu, which was dropped into the sea in 1966 and found on February 3, 1970 and from I Jowett, who was aboard the QE II. However, in some cases the adventure is more fictitious, such as the message from Nat Lovell which included a fake treasure map.

5) Research

The most impressive of the letters must be the two sent as part of scientific studies. The first one recovered, on February 6 1982, was one of three thousand bottles dropped overboard the Sterke Yerke III during an environment-oriented trip during May and July 1979. The project was to study the waste routes of the Rhine. The bottle that landed on the eastern shore of Grand Turk was dropped just south of Gran Canaria at Latitude 25N and Longitude 17W. In addition to this bottle one was found in Anguilla, two in the Virgin Islands, one in Puerto Rico and one in Mexico. We must ask what happened to the other 2994 bottles — did they just become part of the waste at sea?

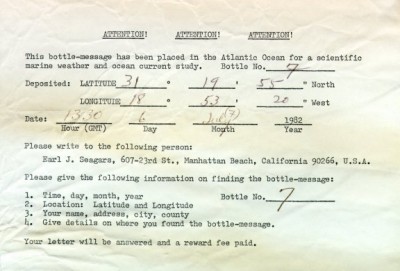

The second bottle with a research orientation was found by a tourist on White Sands Beach, Grand Turk on January 30 1994, and handed it to the Museum. This bottle, number 7, was part of a scientific marine weather and ocean current study. It was dropped on the July 6 1982 at latitude 31, 19, 55 North, Longitude 18, 53, 20 West. The researcher dropped a bottle each day during a voyage from Madeira to British Virgin Islands, 24 in total. Responses were received from Abacus, Bahamas (the bottle here took 10 months to be found), Big Mayors Cay, Exhuma, Bahamas (took 3 years), French shores (3.5 years), Casablanca, North Africa (4 years), Santa Maria, Azores (8 years) and Grand Turk where it had taken 12 years to be found. This was part of a bigger project that included similar experiments in the North and South Pacific Ocean. The researcher, Professor Seagers of the University of California also sent details for the reason for his research. In an attempt to encourage a response the message recorded that a reward would be paid: this turned out to be $5.00.

Message 51 from a scientific research project.

So why are these messages important?

First and foremost they allow scientists to gain invaluable knowledge of the sea currents and drifts. This is important to help predict the most likely place for the debris in the sea to make landfall. But why do we need this information? Have you ever wondered how, after a major disaster such as an oil spill, the authorities can be prepared to move material so quickly to the likely area it will come ashore. Also, in this regard understanding drift allows the coastguards to start a search for missing ships, crewmen and swimmers based on the knowledge of currents.

A second important reason is that it relies on the finder of the bottle to respond. Messages in a bottle are attractive, providing a sense of travel, time and distance. The finder will want to know more about the message, and hopefully the project. The local paper will often get involved to tell the story. This provides a way of informing the public about the problems of waste in the sea without appearing to be preaching to people about the rights and wrongs of dropping rubbish and waste by products from ships into the sea.

In fact, whatever the reason for the initial message Grethe turned it into a research project. She wanted to have as much information about the sender and the route the message took. It frustrated Grethe that she occasionally found bottles that contained either very faded or completely blank messages and in 1980 sent several letters to specialists to find out if there was any way to recover the messages. At that time the responses were negative so the information once held in these messages was lost.

Grethe Seim’s untimely death has brought an end to her collection and the enthusiasm she had shown. However, the Museum staff feels that this is a project that should be continued. It was this collection that inspired the Message in a Bottle project and today the Museum continues to collect messages found on the beaches in the Turks and Caicos Islands.